As early as 1698, as many as 40,000 Chinese immigrants were recorded as living in Cholon (roughly equivalent to present day districts 5,6, and 11), then the largest Chinatown in the world. Known as the Ming-Heung, they were political refugees from the fall of the Ming dynasty, and formed the first intermarried Sino-Vietnamese community in the South. Chinese immigration continued at low, stable levels through the 18th century, despite the massacres of ethnic Chinese that occurred after every intercession of the Qing dynasty into the wars between the various kingdoms and duchies that make up modern day Vietnam, including those of the Trịnh lords, Nguyễn lords, Lê dynasty, and Tây Sơn brothers.

The Tây Sơn army in particular alternately massacred and recruited Chinese, with sanctioned pogroms in 1776, 1783 and 1792. The Chinese community didn’t emigrate; they simply changed their allegiance to the Nguyễn lords. So did the Qianlong emperor, whose troops helped enthrone them as the Nguyễn dynasty in 1802. Under their rule, ethnic Chinese enjoyed equal status under the law.

Currently only 5% of the population of Cholon identifies as Hoa; whoever stayed after the purges during the Sino-Viet war is now completely assimilated. Even so, the halls are still very active. So let’s take a look! For ease of use, I’ve titled them as their name appears on google maps. I’ve also sorted from oldest to newest.

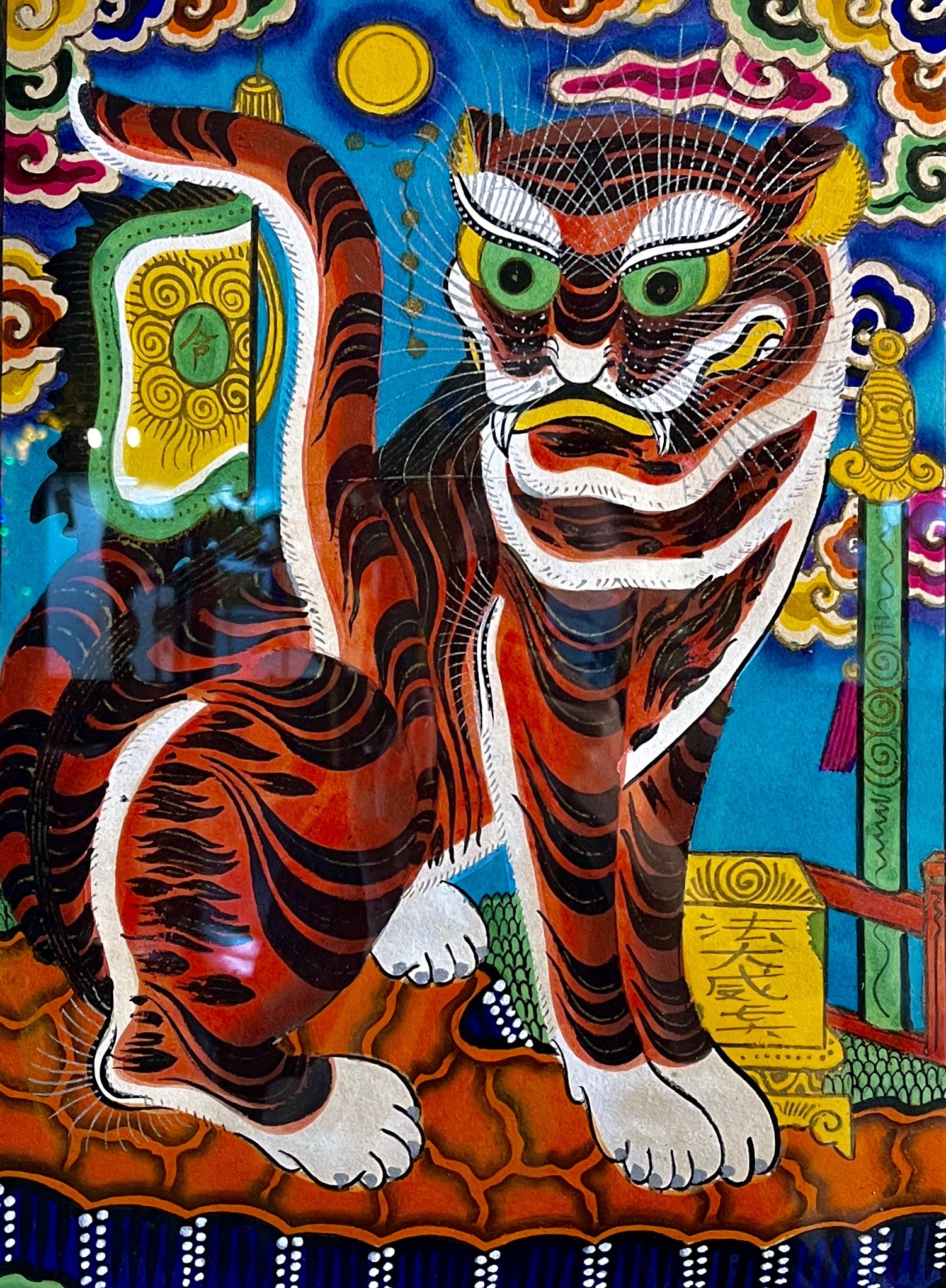

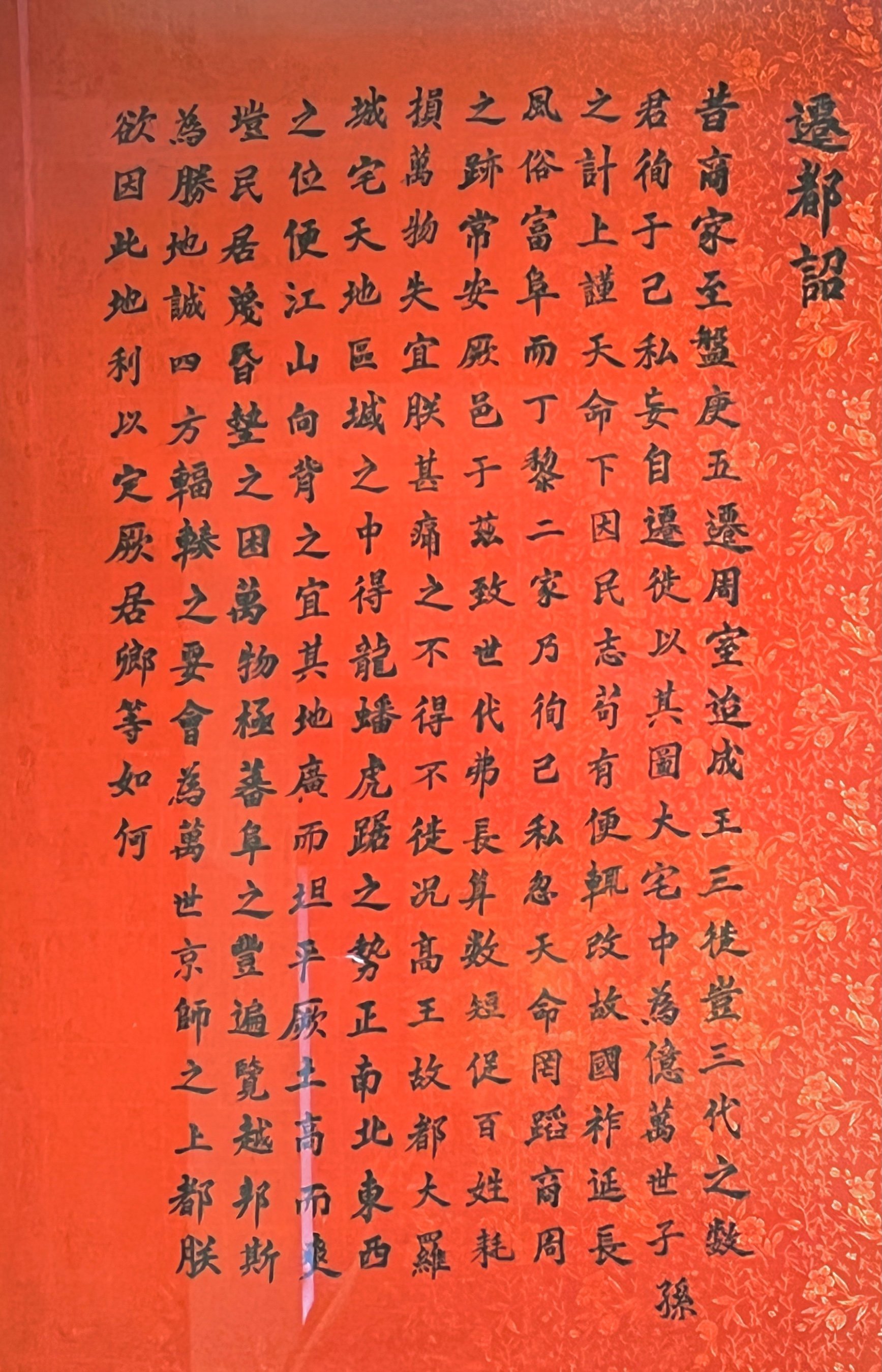

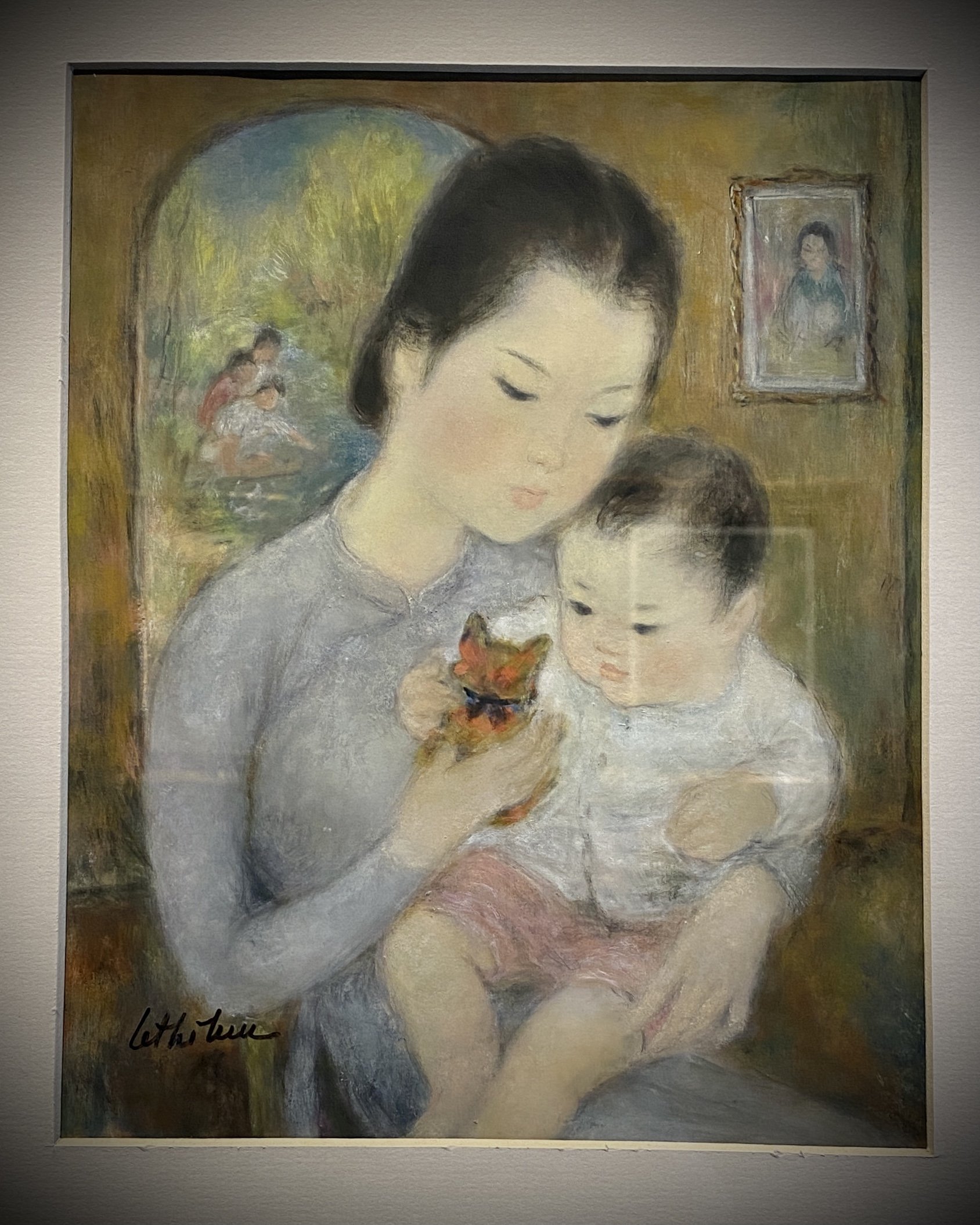

1. Teochew Guan Yu Temple, 1684

(also known as Nghia An Hoi Quan Pagoda, Guan Di Temple, Yian Clan Hall, Ong Pagoda)

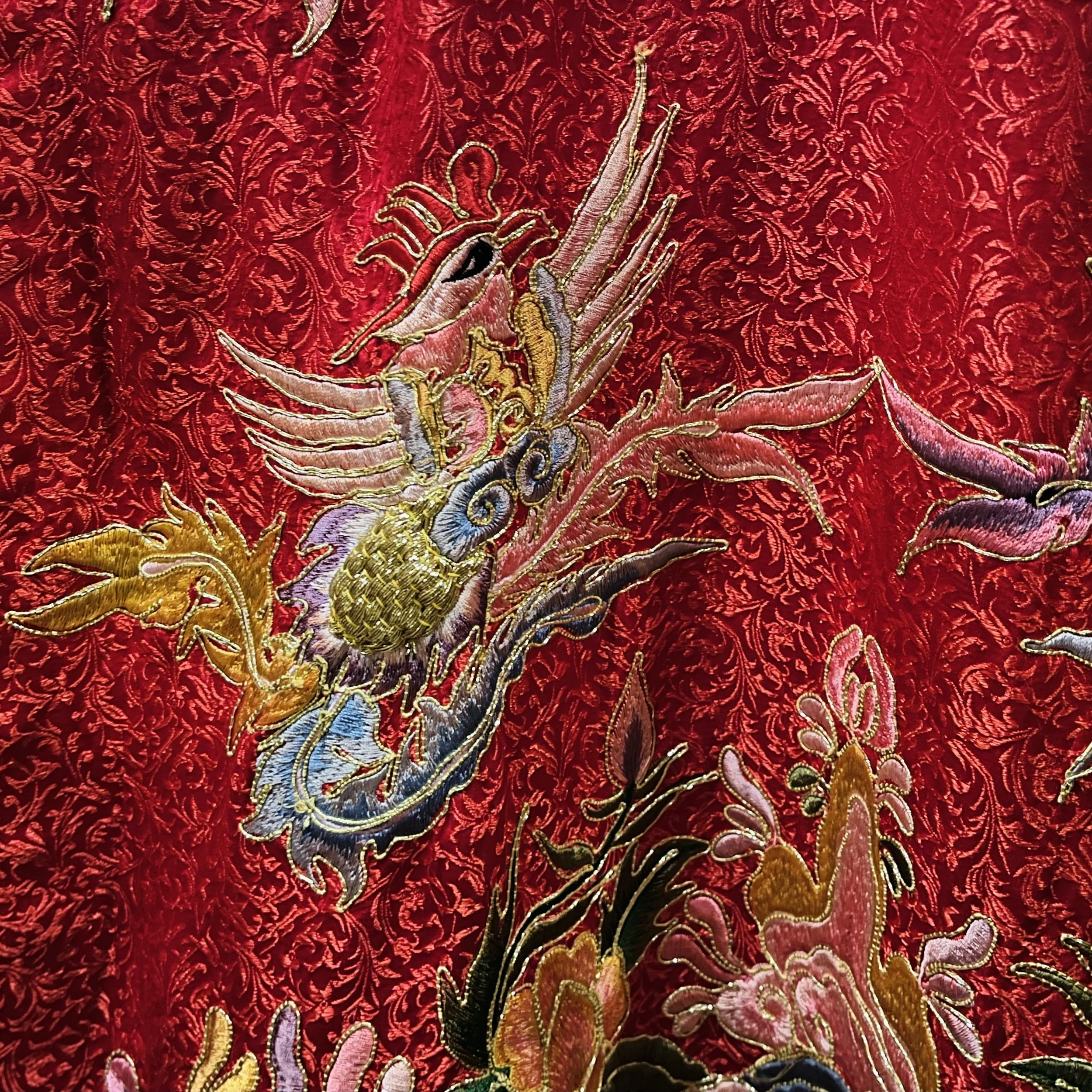

Originally built in 1684 by Teochew immigrants, Guan Di/Yu (the god of war and literature) is worshipped here. The temple is famous for its traditional woodwork. The best night to visit is the 15th day of the lunar new year, when an annual full scale traditional opera is performed.