The Ao Dai museum is 18 km outside of HCMC, around a 45 minute drive. It’s far enough from the city for the sky to actually be vibrant and blue (as opposed to opaque, polluted white) and the layout features several traditional style buildings around a large pond. It’s perfect for an impromptu photo shoot, and several people were around doing just that, taking pictures and sharing their lunches in gazebos. Ducks, chickens, dogs, and puppies are semi-contained in their own areas, but roam with some freedom.

There’s a row of small traditional style two story attached houses, each with traditional costumes specific to a minority group or region, complete with pictures, explanations and even instruments or other props. There’s a hall full of children’s books and art supplies, where I assume activities are held during non-covid times. There are a couple offices, and a couple combo workshop/showrooms where presumably you can order an ao dai; they may be tied to the designer Si Hoang, who owns the place. All of the buildings are constructed with traditional Vietnamese wooden architectural elements in traditional styles, though not wholly so as they are adapted for modern use.

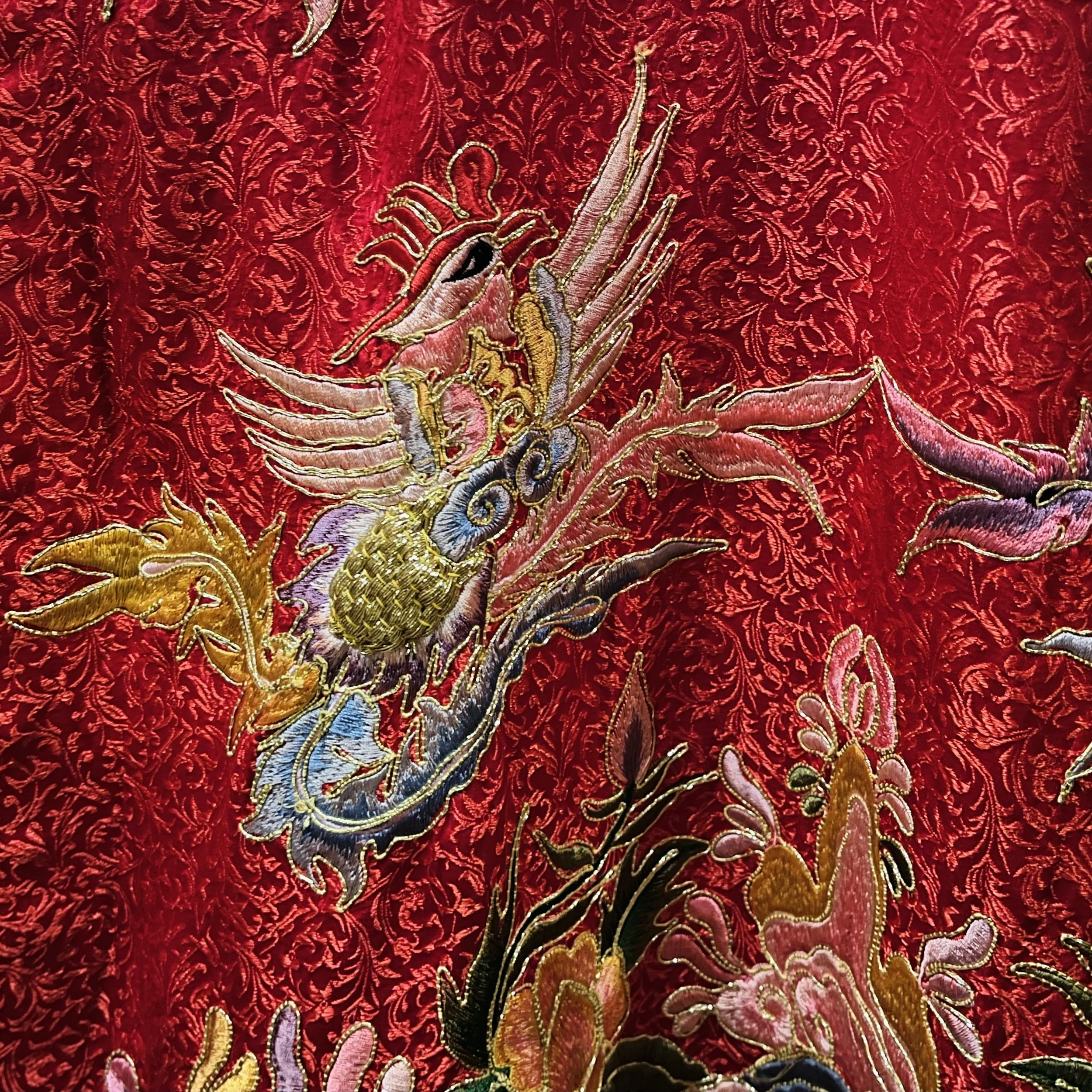

The main attraction is the hall of ao dai, featuring representative historic styles, examples from Vietnam’s current top designers (including more than a few by Si Hoang himself), costumes worn by famous performers of traditional Vietnamese music genres, and costumes or formalwear worn by other famous Vietnamese artists including writers and painters.

Disclaimer: though versions of the ao dai were part of court attire in the Northern and Southern kingdoms, the highly symbolic, rank based and regional nature of court attire is a complex topic deserving of its own post, so it’s not discussed in this one. This post focuses on the ao dai everyday women chose to wear.

Historic Vietnamese dress is generally less well attested than European dress, but extant illustrations and paintings show the evolution of Vietnam’s traditional costume, and how it compares to styles worn in China, Japan, and Korea in the same eras. Recognizable ao dai first appear in the mid 17th century, and are called 4 part ao dai, referring to the 4 pattern pieces of the simple wrap dress. The dress itself was typically brown, and worn over a long black skirt or very loose trousers; older women wore dark colored blouses underneath, while young women and girls wore white or pink blouses. A black waistband was often accentuated with a green or blue silk sash.

The 5part ao dai appeared around 200 years later, and mainly served to signal a higher social class than the 4 part ao dai. The 5th part is a hidden section that served as a combo bra and collar, and the overall appearance of the ao dai resembled Qing Dynasty costume much more closely, wrapping high above the bust, with a mandarin collar and five frog style button closures down the right side. Though the buttons had symbolic meaning (representing the 5 virtues of humanity, civility, gratitude, intellect and credibility), by the 1910s and 20s women were using invisible buttons and snaps instead, as flat hardware-free dresses were considered easier to wear jewelry with.

In the 1930s, Lemur (Nguyen Cat Tuong) became Vietnam’s most famous fashion designer, introducing European styles and trends into ao dai design. For example, you could order traditional narrow sleeves . . . or short sleeves, or puff sleeves, or flared sleeves, or no sleeves! Your ao dai could be short or long, collar or no collar, buttons or no buttons; it could be made for any occasion from a wedding to an afternoon at the beach. His designs were also cut closer to the body (though still loose fit by modern standards) and deemed outré by many. He disappeared at the too young age of 34 (captured by the French militia during their retaking of Hanoi in 1946) making his creations iconic collectibles.

The next lasting change to the ao dai happened in the early 1950s: the tightly fitted, cinched waist look was born, though balanced somewhat by high mandarin collars and generally longer lengths. One of the first fashion-related cultural differences that struck me when I arrived in Vietnam was how it is considered slutty/disrespectful to actually show any skin like cleavage, thighs, or even just shoulders . . . but it’s somehow OK to wear a completely see-through, skin tight ao dai with a brightly colored pushup bra underneath. An acquaintance explained “the Vietnamese woman’s ‘secret’ is to show nothing but reveal everything.”

In the late ‘50s and ‘60s, ao dai became a fashion item, reflecting international trends including boatnecks, raglan sleeves, psychedelic prints, midi lengths, and lots of variation on the trousers (cigarette style, palazzos, bell bottoms etc.) Though Western style daywear had become the norm, the fights for independence and reunification also inspired young people to wear more traditional clothing as a patriotic gesture.

Following Vietnam opening up its economy in the very late 80s and 90s, ao dai became a high fashion item, with domestic designers expanding the role of ao dai beyond costume, formalwear and granny attire. If you’re curious as to who Vietnam’s eminent ao dai designers are today, look no further than the museum’s board of directors: Si Hoang, Minh Hanh, Cong Tri, Vu Viet Ha, Thuy, Nguyen Si Toan, Nga Phan, Nguyen Ngoc Nga, and My Hao.

I found my visit to be a worthy use of a morning despite the hour and half of car time, particularly due to the beautiful scenery. However, if you are a serious textile or fashion nerd, there’s not a lot of info here, even less of it in English, and just one or two examples of each era defining style. So, a nice experience overall, but don’t expect climate controlled displays, acid free swatch albums, etc. There are reference books on display; if I ever find the one about Lemur in a bookshop I’ll definitely pick it up!