The Southern Women's Museum is a no-go, in my opinion. It's made up of two buildings; as of 2023, the main building has been closed for construction for years and the annex is severely mold damaged and reeks, and I'm not sure if that's being addressed properly. The villa next door is also under very loud construction.

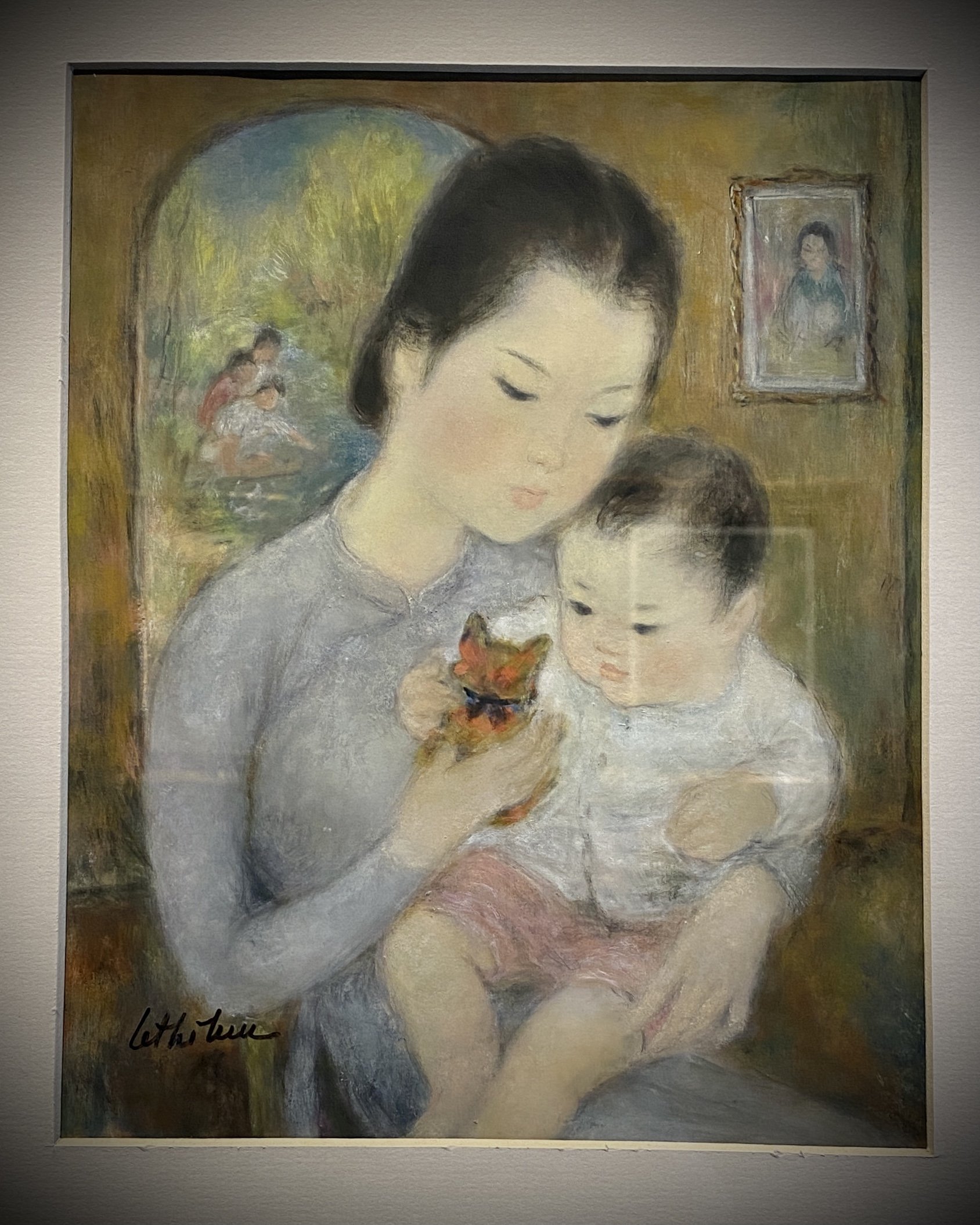

As for the content of the museum, it was incredibly, unexpectedly, one-sided, entirely focused on communist activists operating in Saigon and other Southern cities. It was also totally unconsidered; the tone was very much homage rather than historical examination. The artifacts were sparse.

You can visit in 20 minutes, but in my opinion you should only bother doing so if you happen to be within a 2-block radius; definitely don't make a special trip for this. If you want to visit a women’s museum in Vietnam, make time to see the museum in Hanoi.