Huang Wen Hua 黃文華 was born in 1845 in Fujian province, China. He moved to Vietnam at the age of 18, following the 1860 Treaty of Peking, which allowed Chinese citizens to seek employment overseas. By the time he moved in 1863, Vietnam was freshly colonized by the French and consequently seen as full of business opportunities and relatively safe for Chinese immigrants.

The French privileged these Chinese immigrants over native Vietnamese within their corvee system; between 1870 and 1890 over 20,000 Chinese (mostly single men) moved to Cholon alone, creating the largest Chinatown in the world at that time. In just one generation, a merchant class of wealthy, pro-French, relatively unassimilated Sino-Vietnamese elites was created that held economic control of the south until reunification in 1975.

Huang first changed his name to the rather more Vietnamese Huỳnh Văn Hua, but soon realized it would behoove him to convert to Catholicism and use a French baptismal name. He finally ended as Jean-Baptiste Hui Bon Hoa; Hui Bon Hoa being not only an approximate transliteration of his name as pronounced in his native Hokkien dialect, but homophonous for the French “oui, bon Hoa”. His name taken as a whole, in English, reads: John the Baptist yes good Hoa (Hoa meaning people of Sino-Vietnamese descent).

He became the richest man in Saigon during his lifetime, but still visited China frequently, passing away there suddenly in 1901. He built his business from a single pawnshop opened in partnership with a former French employer to a property development empire; he was known to have owned 30,000 shophouses, as well as hotels, banks, hospitals, etc. His unrealized dream was to build the grandest villa in Saigon, a French style mansion large enough for all of his children and grandchildren to live together. In 1929, his three sons decided to start building the dream; before it was completed in 1934 two of them had also passed away.

Over time, successive generations were educated overseas and emigrated. These descendants still live in France and America today, using Hui-Bon-Hua as their surname. By 1967, the house was seized by the South Vietnamese government. All members of the Hui-Bon-Hua family left before the end of the Vietnam war, and in 1987 the three buildings were officially “donated” for use as an art museum, which opened in 1992.

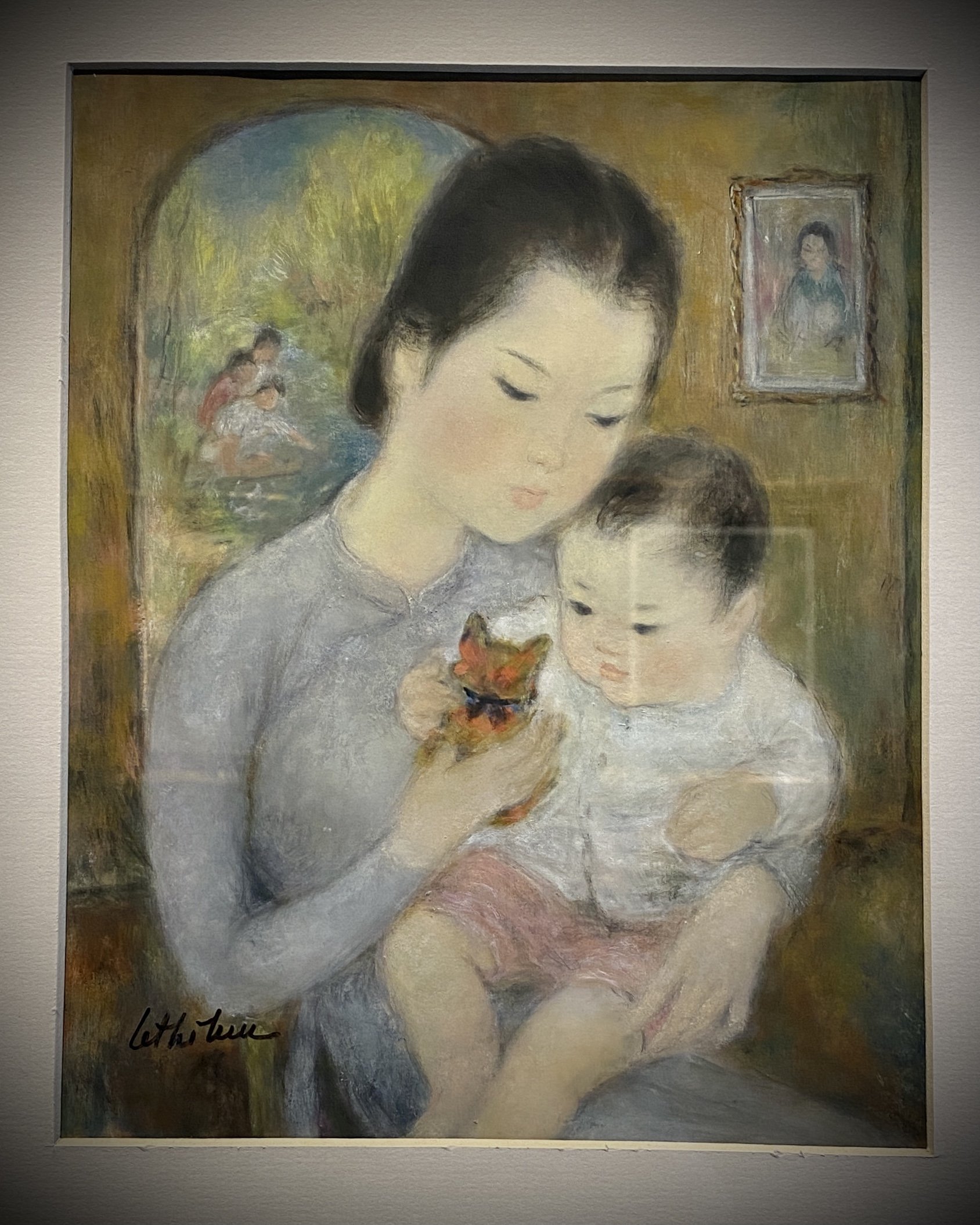

The art here is solely Vietnamese. There are the requisite displays of Cham and Óc Eo artifacts, plus traditional Vietnamese styles like monumental lacquer paintings and paintings on silk. The most famous artists in Vietnam are shown here, as well as artists in the Vietnamese diaspora. I have zero knowledge of Vietnamese art or artists, and found the works of Lê Thị Kim Bạch, Trần Việt Sơn, Huỳnh Quốc Trọng, and Nguyễn Minh Quân compelling.

As in Hanoi there are umpteen war pictures, yet not a single one depicts an ARVN flag, despite this being the South. Money is too new in Vietnam for there to be any grand patrons of the arts just yet . . . if there are any Picassos or Chenghua porcelains in Vietnam, they are in private homes.

The museum doesn’t take more than a day to explore fully. I wish there was an onsite cafe, but I survived. I’d also advise against buying anything on nearby Antique Street, it’s all fake. If you want to buy an authentic work, there’s a selection of antique porcelain and some lithographs and watercolors in the museum’s ground floor gallery. They also have the best selection of books on Vietnamese art and artists that I’ve come across.