After fruitless hours searching for the elusive “Mr. Rivera”, the supposed French architect of the Hui Bon Hoa complex, I was surprised to find the life and career of Auguste Delaval, architect of the HCMC History Museum, so thoroughly attested and accessible. His many prize-winning watercolors and gouaches of Indochina are held in his hometown museum in Hennebont, France; scans of his transcript at the École des Beaux-Arts are a simple google search away.

The History Museum and the Museum of Cham Sculpture in Da Nang are the two buildings outside France that Delaval remains known for today; the history museum, built between 1926 and 1929, is undoubtedly his best extant building. He was among the clique of architects typically competing for Indochinese colonial commissions, including Vildieu, Moncet, Bussy, and Hébrard. He submitted designs for lots of institutional jobs he didn’t get; the Dalat train station, for example, went to Moncet. Each firm had a side business in privately owned luxury villas, since they knew how to build in Indochina; most of the current non-French, non-original owners of these buildings have no idea who their architect was.

Incidentally, I think that’s what happening with the Hui-Bon-Hoa property: Given their differing styles, I think each building was actually built by a different architect, perhaps even from old or previously incomplete plans. For example, I can’t find any Beaux-Arts graduate named Rivera, but the first building constructed (originally the company office, currently the building on the left when you walk through the gate) looks like the work of Gustave Rives, the go-to man for classy Parisian apartment buildings, museums, and townhouses at the time of Hui Bon Hua senior’s death in 1901. If I was the richest man in Saigon, a rental real estate magnate, and a naturalized French citizen, that’s certainly who I would choose.

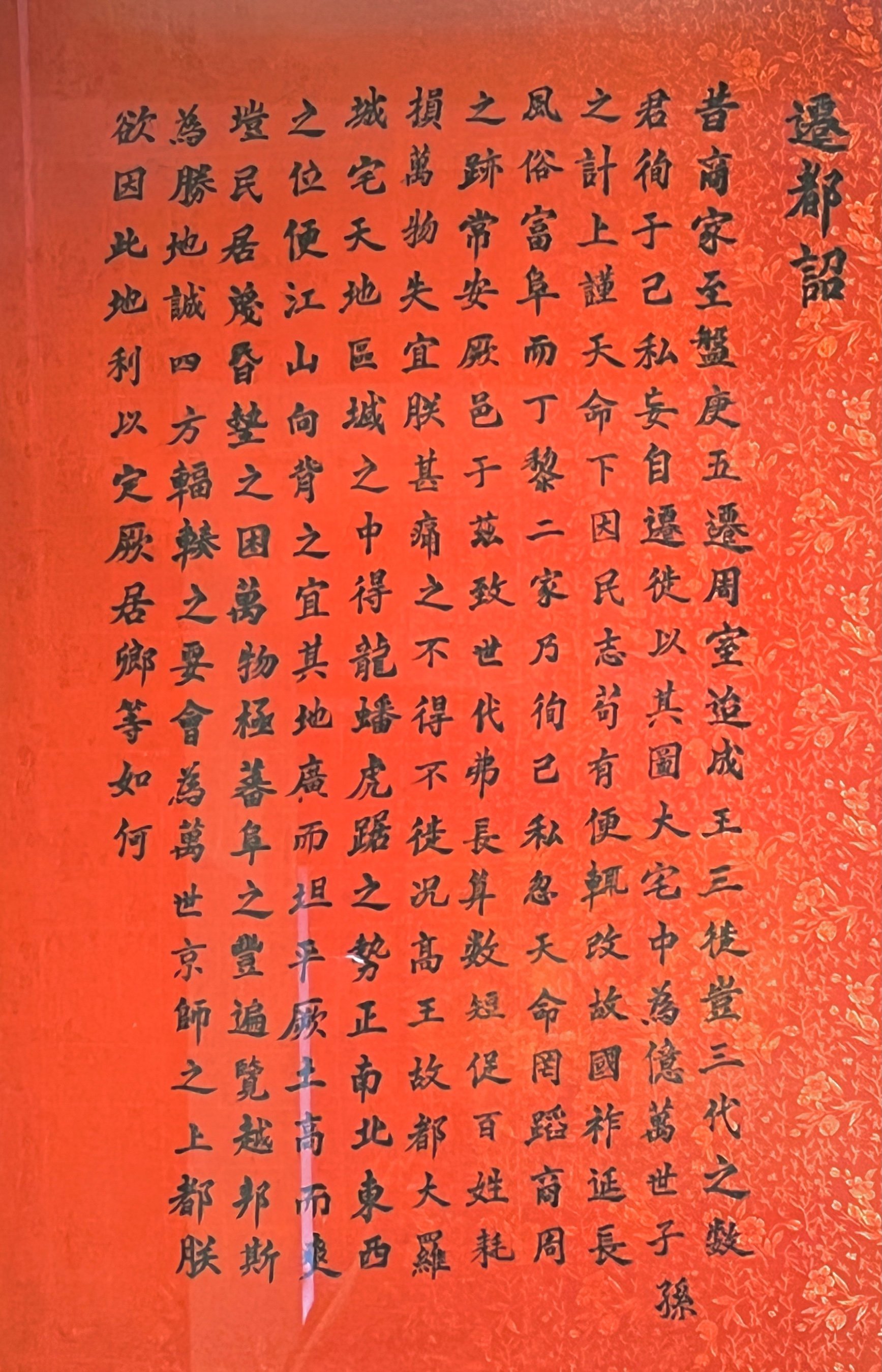

But back to Delaval and the history museum! It was his last institutional building in Indochina; he designed both the main museum building and the adjacent Hung King temple. If it seems odd to you that a Frenchman would be tasked with designing a Hung King temple, you are right: it was originally the Temple du Souvenir Annamite, built to honor the 12000+ Indochinese colonial troops who gave their lives for France in World War 1. It was paid for by public subscription of wealthy Vietnamese, but rededicated nonetheless after the French withdrawal from Vietnam in 1955 (a tasteless act of erasure, in my opinion). The bronze elephant in the adjoining garden has nothing to do with the zoo next door; it was a gift made in 1930 by the Thai King Rama VII to symbolize the troops never being forgotten.

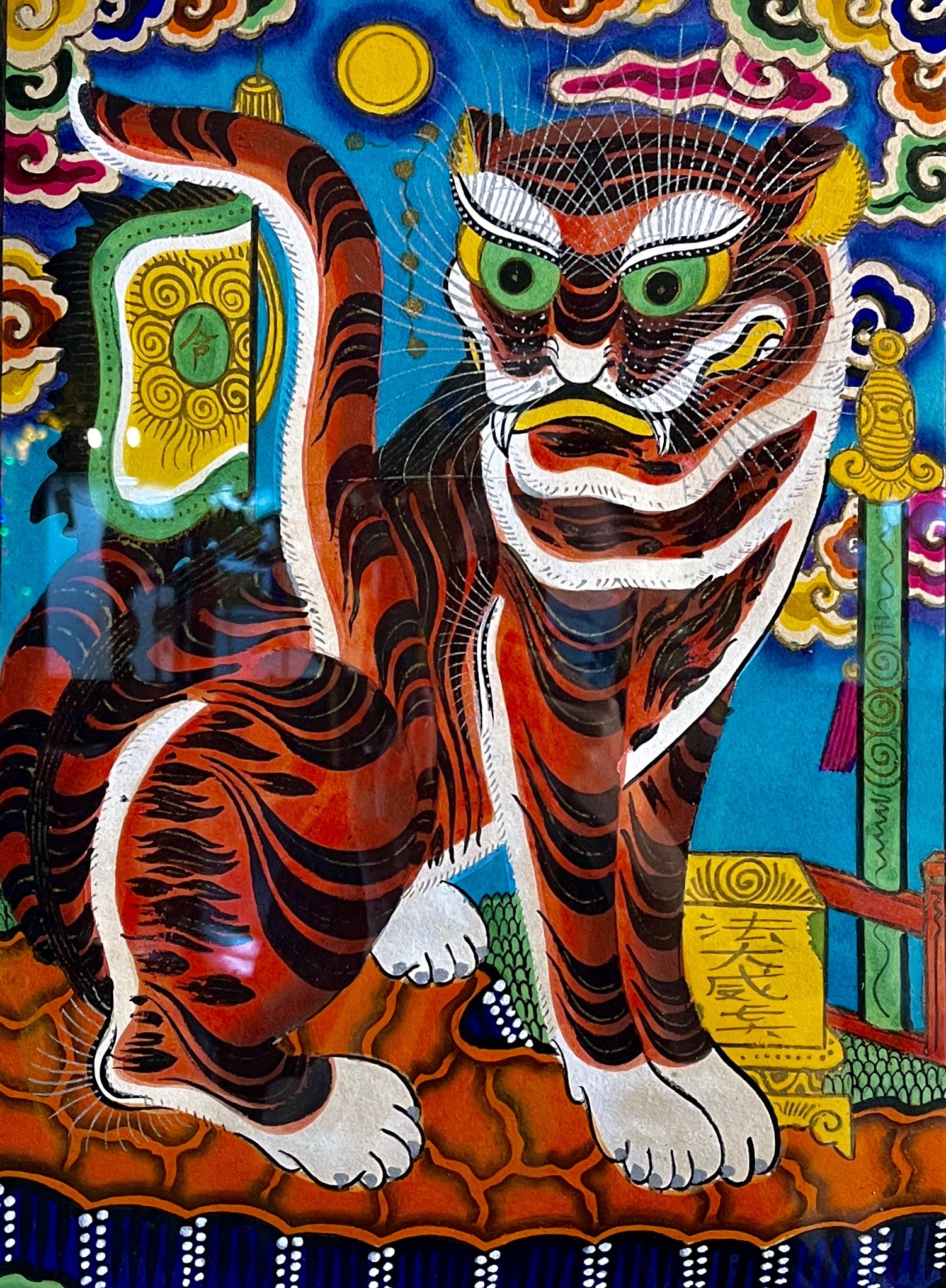

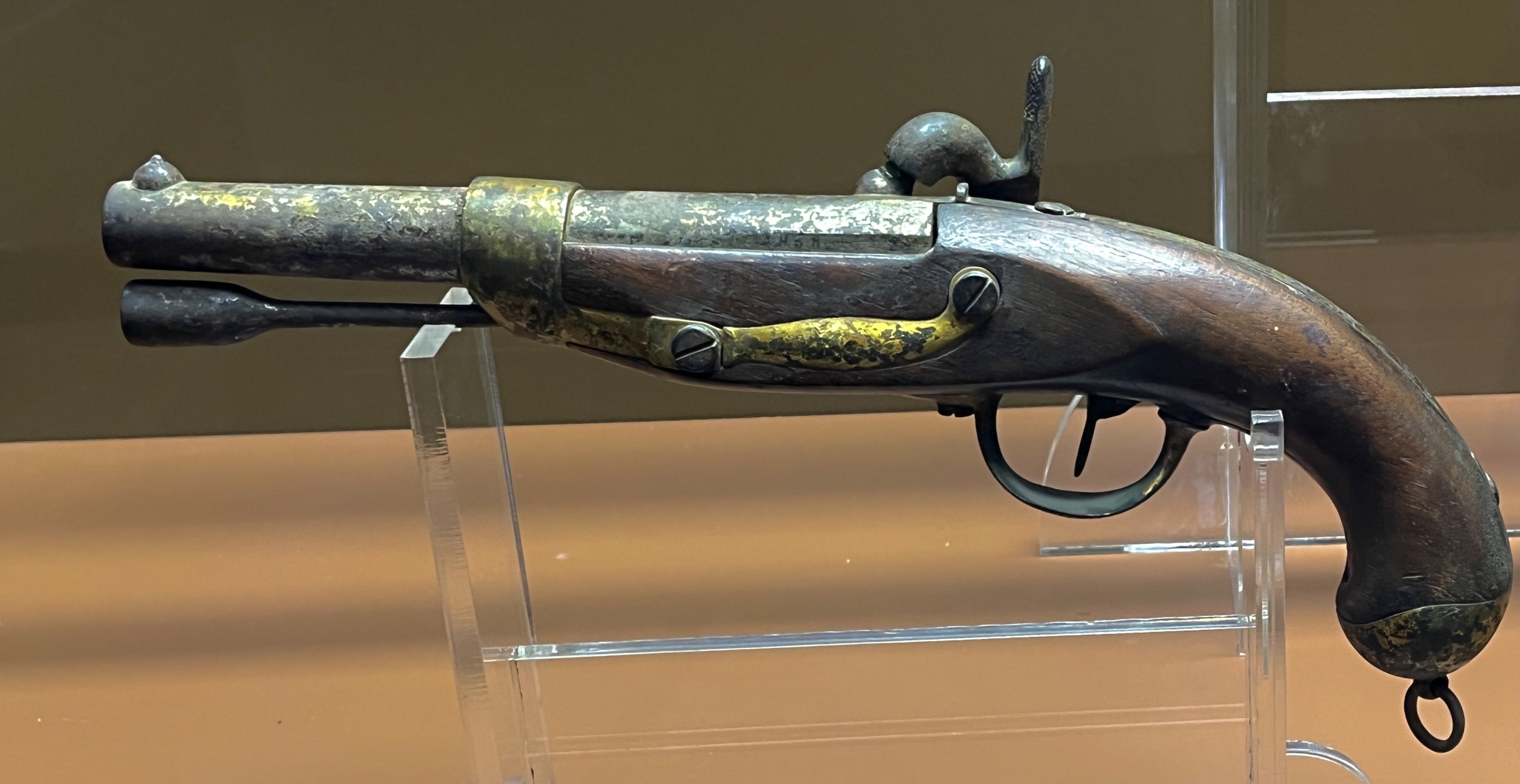

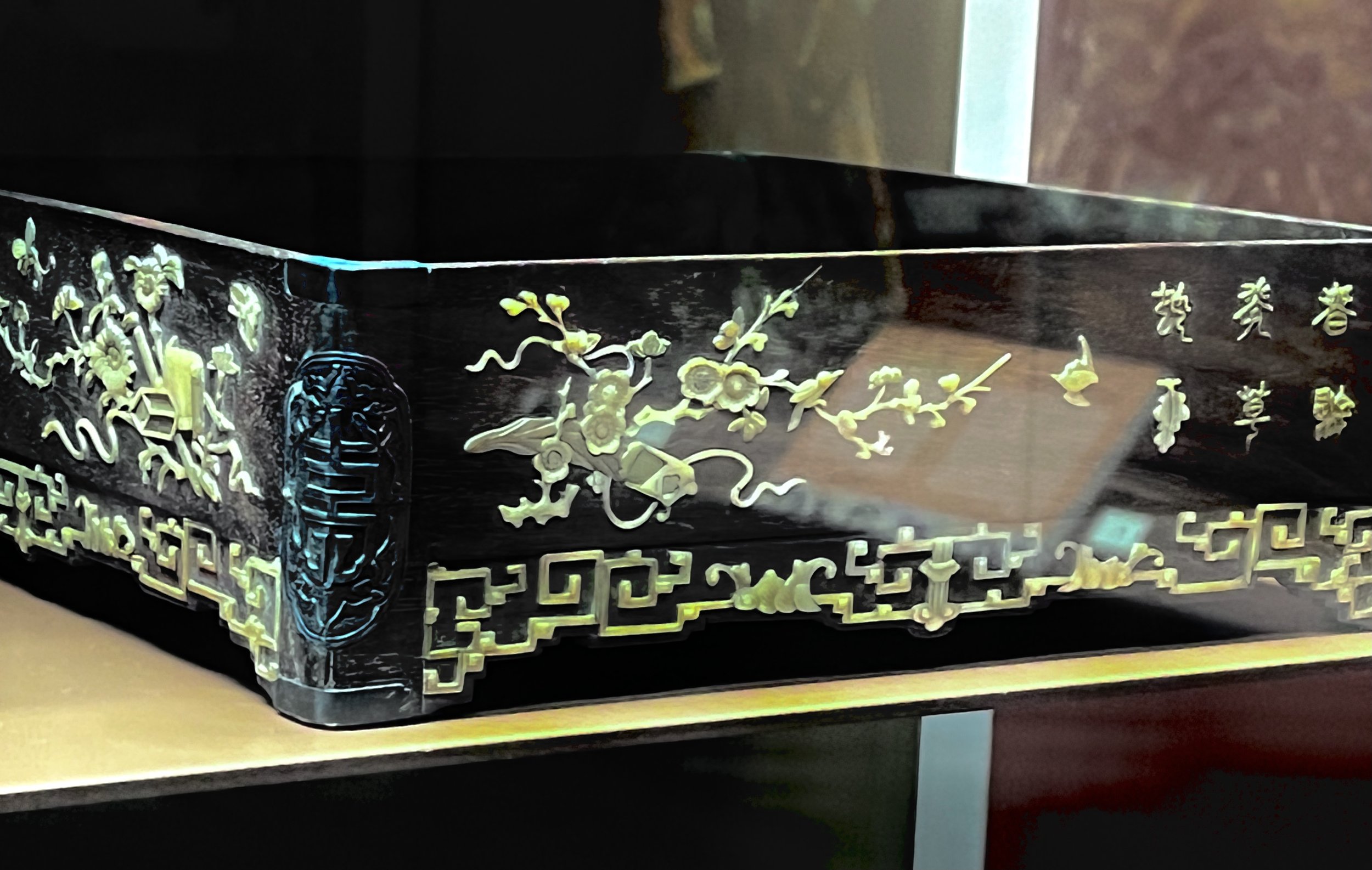

The museum itself is a jewel box. Though the façade is grand, the museum is small, and the interior of the building has an intimate quality; the rooms aren’t overly large, but have very high ceilings with overhead windows or vents. The museum covers the entire history of Vietnam, from prehistory to the current era. It has only a few examples pertaining to each important theme or period, but each example is the absolute best. I was particularly impressed by the quality of the Buddhist relics, ethnic costumes, and Cham and Óc Eo sculptures. It also inexplicably houses an ancient mummy and a second-rate collection of antiques left by a local collector and prolific author on the topic.

As for the temple, it’s been locked for two years now due to Covid; my videos are peeking through the door slats. I was impressed by how totally authentic the materials, construction, and decorative workmanship are: undoubtedly made for and by Vietnamese people. The mark of the French architect is solely in the proportions: it is a cube rather than a long, low, building, with lots of daylight coming in through openwork friezes just below the roof. Relative to old, totally Vietnamese temples, it feels very tall and flat; the columns are more slender, the carvings more shallow.

The proportions and decorative motifs remind me strongly of Emperor Khải Định‘s tomb in Huế, which began construction in 1925 and finished in 1931, concurrent with the museum. It’s quite possible Delaval had an unacknowledged hand in that tomb’s architecture: thought it’s current Vietnamese practice to deny credit to French architects and artisans wherever possible, the tomb is widely admitted to be inspired by the Emperor’s visit to the 1922 Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles, at which Delaval’s scale model of Angkor Wat was the star exhibit. Delaval also had many watercolors of Indochinese architecture, both native and colonial, shown there; he was commissioned by the French colonial government to design this history museum and adjoining (now destroyed) art galleries as a result. It’s not too much of a stretch to think the Francophile emperor hired him to design or collaborate on his biggest commission as well.

If you wish to plan your trip on a tight schedule, the museum website is rather detailed and helpful. However, it shouldn’t take more than two hours to thoroughly review the entire collection. I recommend visiting the museum in the morning before your attention wanes, and visiting the zoo afterwards. Also, be prepared to feel a bit miserable: there is no air conditioning, there are lots of mosquitoes, and the adjoining cafe is cash-only and allows smoking. Admission costs less than $2.