Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu | India

Colin MacKenzie, 1808

Mahabalipuram, also known as Mamallapuram (plus, historically, Mahabalipoorum, Mahavellipore etc.) is always described in British colonial records as ‘a tiny village south of Madras,’ and remains so, with a population of around 12,000, though it was once the first or second largest port city of the Pallava empire. Its name is derived from the title 'Mahamalla' (meaning Great Wrestler) of the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I (ruled 630-about 668 AD). Traditionally, the archaeological sites there, most notably the monoliths, have been mostly attributed either to his reign or that of his son, but more recent research suggests his grandson, Rajasimha (r.c.700-728), who benefited from a long reign over a peaceful empire, is responsible for the structural temples at minimum. The temples remained largely untouched until the 1850s, when archaeology and photography were simultaneously quickly advancing as disciplines, and the British began to photograph and excavate the site. Now, it’s a cleaned-up tourist attraction with many sites handicap accessible from the main road.

The Archaeological Survey of India has posted some great 3d images and the basic facts here on Google Arts & Culture: https://artsandculture.google.com/story/mahabalipuram-sculpture-by-the-sea/_wXB5vhuL90aJA

It was difficult to wade through the piles of low-quality, low info, non-English videos about Mahabalipuram; this is the best synopsis by far. I recommend watching it before visiting, perhaps on the car ride over.

A ticket for all the temples is currently 30 rupees for Indians, and an outrageous 600 rupees for foreigners, or about $7.25. It is an easy stop when driving between Chennai and Puducherry, but, in my opinion, it’s something of a myth that the sites can be visited in a day. Perhaps if you arrive extremely early and leave quite late; they do light up the Shore Temple in the evenings and continue to sell tickets there after sunset. Personally, I made two roughly 3-hour stops and still feel I didn’t see everything thoroughly.

Sunscreen, and a hat and/or umbrella are an absolute must: there is no shade from trees, not a single gazebo, and the temperature hits 30 every day of every month except December and January. You’d also do well to bring lots of water bottles, as the roadside vendors seem to exclusively sell very overpriced, very likely refilled bottles and warm sugary sodas. The bathrooms are pretty gross, I recommend bringing wet wipes, sanitizer, and a little garbage bag to clean your privates and your feet. India doesn’t have minimart chains like other parts of Southeast Asia, so you won’t see anywhere to stop and buy basics just driving through the village, you have to come prepared. There is one old man chopping coconuts across from Arjuna’s Penance, thankfully- without him, I would have fainted twice over.

A fully charged phone, camera, and extra batteries and charging banks are also a must; businesses in India never have working electric outlets for the convenience of customers, it is nothing like other countries where you can expect to charge your phone while eating at a restaurant or while shopping around, and drivers never have anything but jacked up old usb chargers in their cars, because very few Indians can afford nice phones. Speaking of dining and shopping, don’t bother. Bring snacks in the car if you need them. The village is a walk away, and it’s hard to even find a restaurant with seating and a fan among all the tourist tat shops, there’s certainly nothing air-conditioned.

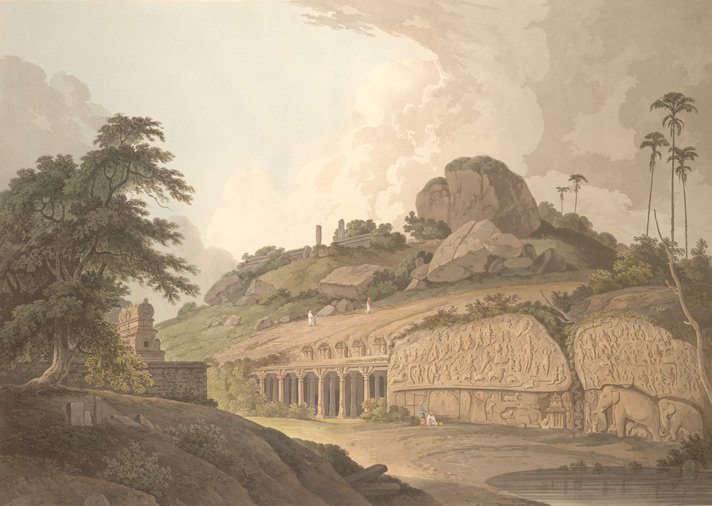

plate 1 from the fifth set of Thomas and William Daniell's 'Oriental Scenery' called 'Antiquities of India,’ 1799

plate 21 from James Fergusson's 1839 'Illustrations of the Rock Cut Temples of India'

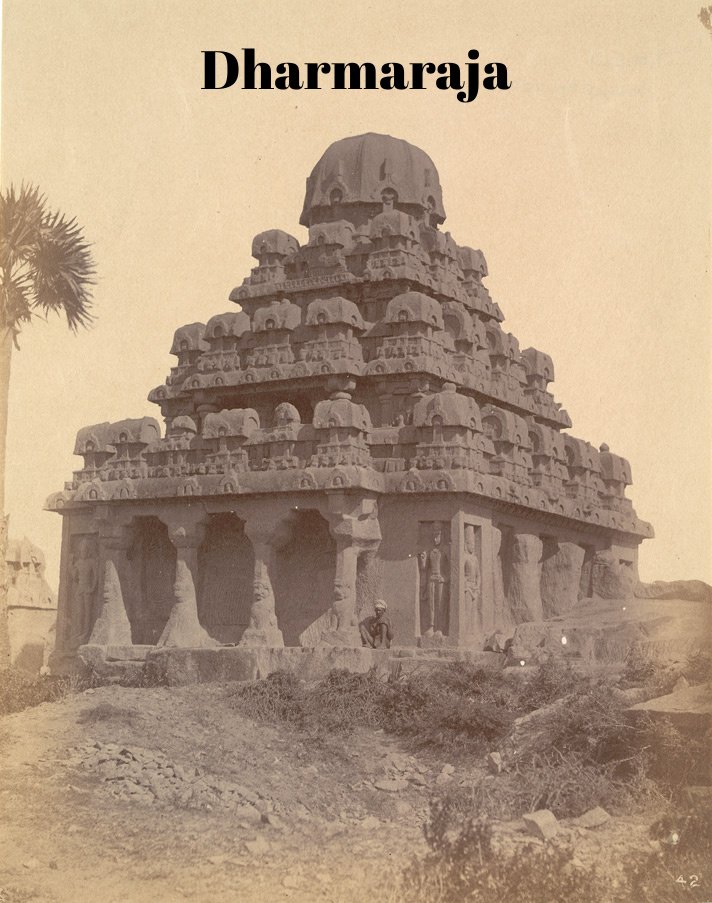

The first of the archaeological sites is the Pandava Rathas (Five Chariots), five monolithic temples hewn from granite between 580 and 720 CE: the Draupadi Ratha, the Bhima Ratha, the Dharmaraja Ratha, the Nakula and Sahadeva Ratha, and the Arjuna Ratha, named after members of the Pandava family in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. Their shapes represent the earliest examples of monumental architecture in southern India; each is unfinished and in classic Pallava style, appearing to have been purposely built as models that provided the templates for subsequent religious buildings in south India. They are remarkable for their variety in plan, architectural style, and elevation, as they imitate in stone the earliest wooden temples.

Francis Frith, c.1860

The Draupadi ratha (left) resembles a wooden hut with a thatched roof and has female guardians between pilasters on each side of the doorway. It is dedicated to Durga. The Arjuna ratha (right) is similar in form to the larger Dharmaraja ratha on the same site, with a two-storied pyramidal roof and octagonal dome, and is assumed to be dedicated to Shiva.

The Nakula Sahadeva Ratha could be associated with either Indra or Aiyanar, as they both ride elephants. The style of building is rare, and is called ‘elephant back.’ The entrance portico has two monolithic columns with seated lions at the base.

Francis Frith c. 1860

Francis Frith c. 1860

The Bhima Ratha is rectangular and crowned with a barrel-vaulted superstructure, resembling a Buddhist chaitya, and is associated with Vishnu. It is incomplete in its lower level. The entrance portico has four free-standing columns with seated lions at the base.

1911postcard

The multi-tiered Dharmaraja Ratha is the most complex of the temples, has a taller pyramidal roof than the Arjuna Ratha, and honours Shiva, Parvati and their son Skanda. It is crowned with an octagonal domed cupola. The porch has columns with lion bases and leads to the sanctuary. The outer wall has sculpture panels depicting various Hindu gods and devotees. The roof-storeys are ornamented with miniature buildings representing the mythical dwellings of Shiva and the gods in the Mount Kailasa.

Francis Frith, c. 1860

Plate 2 from the fifth set of Thomas and William Daniell's 'Oriental Scenery' aquatints called 'Antiquities of India,’ 1799

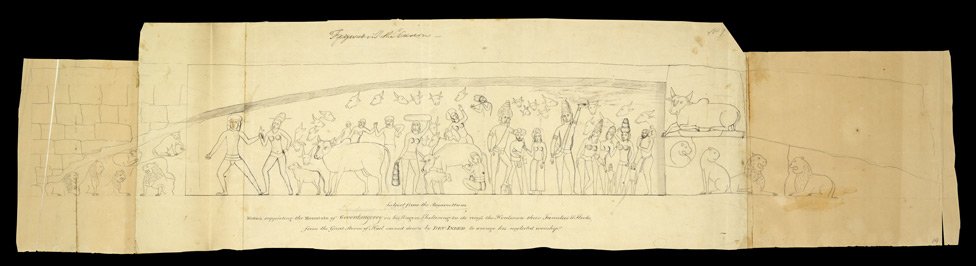

John Gantz, c. 1825. Inscribed: 'A view of the Sculptures representing the tapass or intense penance of Arjoona Mahabalipoorum from a Sketch by Mr J. Braddock. J. Gantz'.

c. 1850s

Francis Frith c. 1860

1860

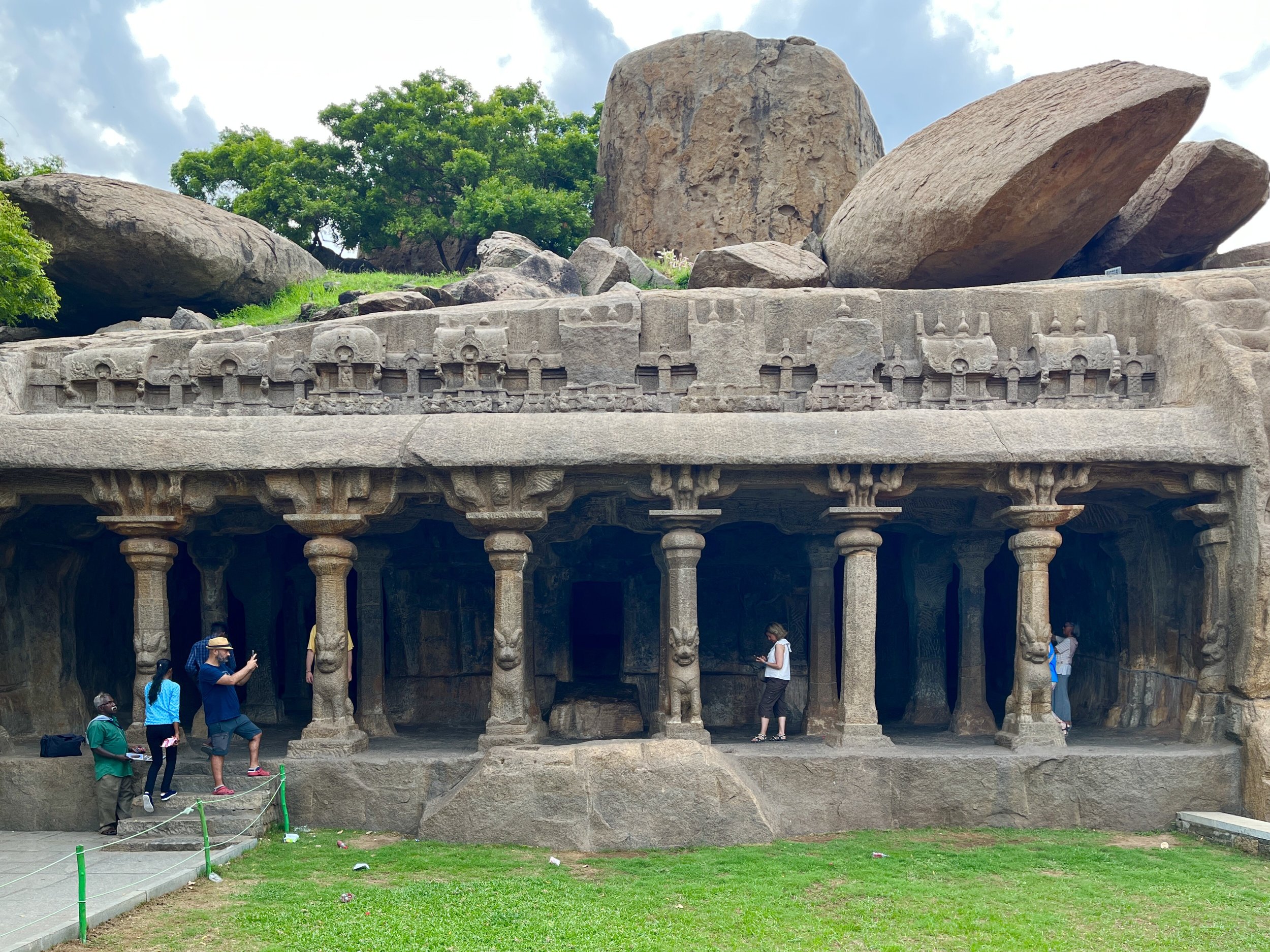

The next (and most famous) site is the Arjuna’s Penance frieze, also called Descent of the Ganges. The cave temple on its left is called the Pancha Pandava Madapa. It’s both the largest cave temple in Mahabalipuram and one of the finest examples of ancient Vishwakarma Sthapathis, rock-cut cave architecture dedicated to Vishwakarma, the craftsman god.

1885

There are six lion-based pillars on the front façade of the cave, apart from two pilasters at both ends abutting the rock. As compared to other caves there is an improvement in the layout and the architectural elements that have been carved in the cave.

One such feature is the intended (the cave was left unfinished) circumambulatory passage; within the cave, there is a long chamber with a second row of four pillars and two pilasters. To the back of this second veranda there is a small chamber cut in an octagonal shape flanked by two niches; it is inferred from this that the intended purpose was to carve this chamber to a square plan and make a passage behind it for circumambulation. However, only a small chamber has been carved at the centre, which has remained attached to the main rock.

At the entrance, the curved cornice has a series of shrines with the four central shrines projecting out. The vaulted roofs of the shrines are carved with kudu horseshoe-arch dormer-like projections, and each shrine houses another smaller shrine. The niche below the kudu has a carved deity.

Another impressive feature is brackets with lion caryatids over the pillars forming the facade; each caryatid consists of three lions one facing to the front and the other two facing to the sides without a lion on the backside. Additionally, the brackets above the capitals of the pillars have decorations of griffins with human riders.

Nicholas & Co. 1880

Alexander Rea, 1885

Pen and ink drawing by Colin MacKenzie c. 1780-1820.

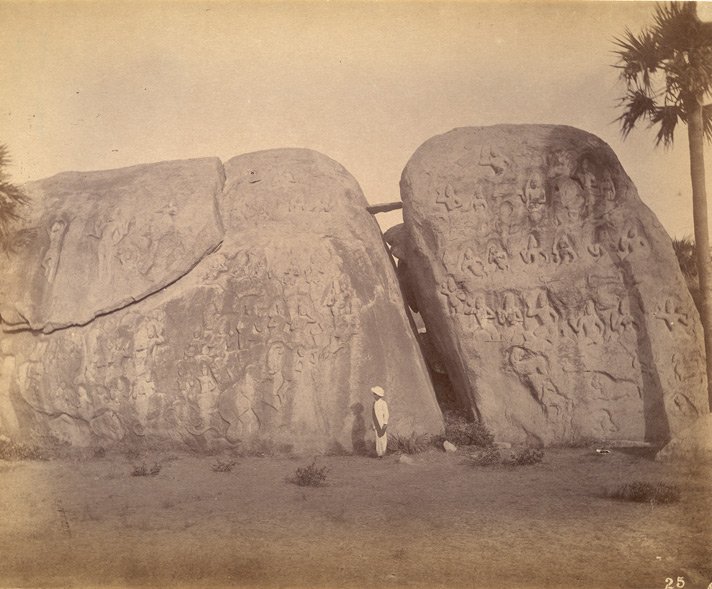

The large relief sculpture (covering two huge boulders 27 m long and 9 m high) was at one time thought to depict the myth of the origin of the river Ganges, in which the sage Bhagiratha undergoes penances while praying to Shiva to catch the river Ganga in her matted locks as she descends to earth, with all the animals and myriad beings watching the miracle. Now, it is more widely thought to represent the story of the penance of Arjuna, one of the heroes of the Mahabharata, undertaken to win the magic axe of the god Shiva. On one hand, Arjuna can be seen standing on one foot while Shiva is holding the magic weapon he hopes to obtain. On the other, the cleft in the rock covered with nagas (serpent deities) over which water used to flow could represent the descent of the celestial river. Scholarly analysis allows for both interpretations of the sculpture, which is anyway considered above all to be a eulogy through mythology of Narasimhavarman I, its probable patron.

Edmund David Lyon around 1868, from an album of ‘Photographs to Illustrate the Ancient Architecture of Southern India’ (vol. V).

Alexander Rea, 1885

Historically called Vaan Irai Kal, which translates from Tamil as "Stone of Sky God," this naturally balancing boulder was later coined “Vishnu’s Butterball,” then perhaps mistakenly called “Krishna’s Butterball” by Indira Gandhi during a 1969 visit, and has been known as such ever since. The boulder is approximately six metres (20 ft) high and five metres (16 ft) wide, and weighs around 250 tonnes (250 long tons; 280 short tons). It seems to float and barely stand on a slope on top of 1.2-meter (4 ft) high plinth which is a naturally eroded hill. According to ancient records, it has been in this shape and place for around 1200 years.

Francis Frith c. 1860

Nicholas & Co., 1875

Nicholas & Co., 1875

Francis Frith c. 1860

Alexander Rea, 1885

The Ganesha Ratha is one of 10 pink granite rathas in Mamallapuram. Originally constructed with a shiva linga which was removed by villagers in the 1880s and placed under a nearby tree, it is now dedicated to Ganesh.

It is built to a rectangular plan which measures 20 by 11.5 feet (6.1 m × 3.5 m), and is 28 feet (8.5 m) in height on the exterior. The interior rectangular chamber measures 7 by 4 feet (2.1 m × 1.2 m), and is 7 feet (2.1 m) in height. The ratha is three-tiered; the façade is a columned verandah flanked by sculptures of dwarapalakas (guardians). The columns are mounted on seated lions, as are the two pilasters. The cornices above the pillars have kudu (horse-shoe shaped dormer windows) depictions along their entire length, and these kudus are also depicted at the gable ends of the roof. Below the gabled roofs, on both long ends, windows are carved in horseshoe shape with three doors, the central door having a sculpture of a human head with a trident akin to Shiva. At the other end of the gable, this sculpture is missing. In the back wall between the pilasters, images are not carved. The roof covering above the top floor is large, vaulted, and wagon-shaped, with arches at the corners. The top of the vaulted roof is fitted with a series of nine vase-shaped finials each consisting of a pot and trident.

There are 18 inscriptions in Grantha and Nāgarī scripts of the Sanskrit language inscribed on its west portico. Out of the fourteen verses in these inscriptions, the twelfth verse is ascribed to Narasimhavarman I's grandson, Paramesvaravarman I, surnamed Atyantakama, who as the Pallava king was known as Atyantakama, Atyantakama-Pallaveshvara-Griham. Other verses are in praise of Shiva.

Colin MacKenzie, 1816

c. 1850s

Francis Frith c. 1860

from the Album of Miscellaneous views in India, 1860s

The Varaha cave is the oldest monument in Mamallapuram. The mandapa is of relatively small dimensions and has a simple plan. The fluted columns separating the openings have cushion-shaped capitals and seated lions at the base. The combination of architectural motifs and depiction of figures not seated in the traditional Indian cross-legged style is believed to indicate Greco-Roman influence.

At the center of the rear wall of the mandapa, opposite the entrance, guardian figures are carved on either side of a shrine. Inside the mandapa, the walls have four large sculptured panels, good examples of naturalistic Pallava art. The side walls have carved sculpture panels of Vishnu: as Trivikrama (Vamana), the lord of three worlds, and in the form of Varaha, the boar, lifting Bhudevi, the earth goddess, symbolically representing the removal of ignorance from human beings. In this panel, Varaha has four hands; his two rear arms carry shankha and chakra, while his front arms carry Bhudevi.

The Gajalakshmi panel on the rear wall depicts Gajalakshmi, an aspect of Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity. She is shown with her hand holding lotus flowers, with four attendants. Two royal elephants are filling the water vessels held by the attendants, another elephant is pouring water from the vessel on Lakshmi and another is about to take the vessel from the maiden's hand to pour water over Lakshmi.

Another panel is of Durga slaying the demon Mahishasura, depicted as a human with a buffalo head; the scene represents a battle between good and evil, with Durga and his confident-looking ganas advancing, and Mahishasura with his army of asuras (demons) retreating. The Brahma panel is carved with Brahma having three heads in sambhaga or standing posture.

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Alexander Rea, 1885

Alexander Rea, 1885

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Mafred Sommer, 2015

John Gantz, 1825

The large, unfinished royagopuram atop the hill is very different from the other shrines in that it was built around 700 years after the rest, during the high point of the Vijayanagar (Karnataka) Empire. Like the royagopuram in Madurai of the same era, it also was left unfinished. According to Linnaeus Tripe, the official photographer of the Madras government from 1856 to 1860, a local saying was “you have laid the foundations of a Raya Gopuram,” to tell someone they’ve started something they can’t possibly finish.

There are several carved cisterns, all seemingly called ‘Draupati’s bath.’

courtesy AMJShots.in - he has also written a very good blog about visiting Mahabalipuram and its history/architecture

Dharmaraja’s Throne features a potentially east asian inspired rock cut bed with a lion resting atop. It is situated to look out along the Bay of Bengal.

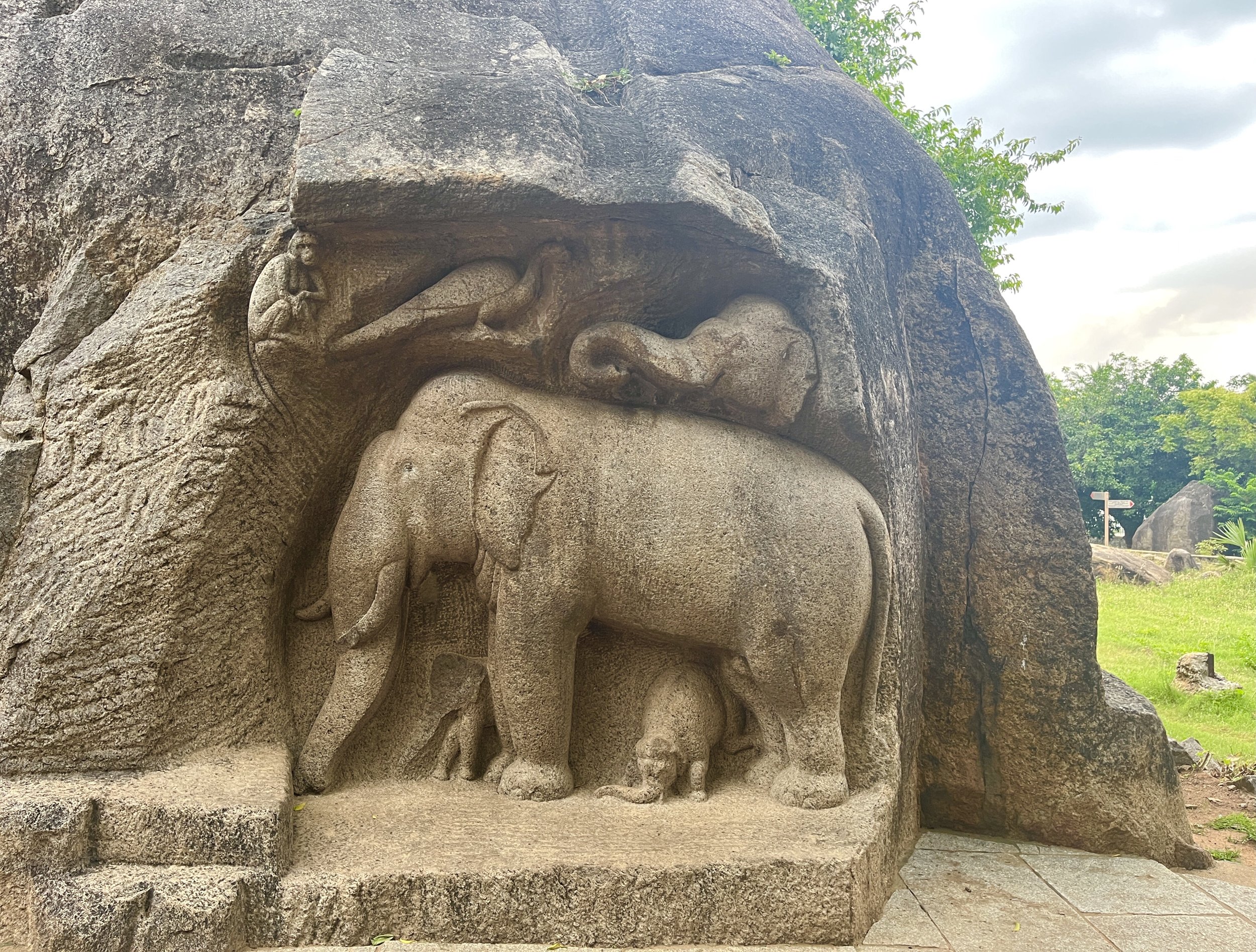

The hill is sprinkled throughout with giant granite boulders and occasional unfinished carvings of great sensitivity, even in examples of little or no religious significance. The baby elephant tripping over its mother’s foot and the monkey’s unimpressed little scowl here are great examples.

from an album of 37 drawings of the temples and sculptures at Mamallapuram, 1816

The Trimurti cave is unique in two ways: first, it doesn’t have a veranda, you enter directly into each of three shrines; second, although it is a classic Brahma/Shiva/Vishnu triple shrine, Brahma appears as either Subramanya or Brahmasasta (scholars disagree).

Manfred Sommer 2015

Manfred Sommer 2015

Alexander Rea, 1880

Francis Frith c. 1860

Manfred Sommer, 2015

plate 20 from James Fergusson's 'Illustrations of the Rock Cut Temples of India,’1839

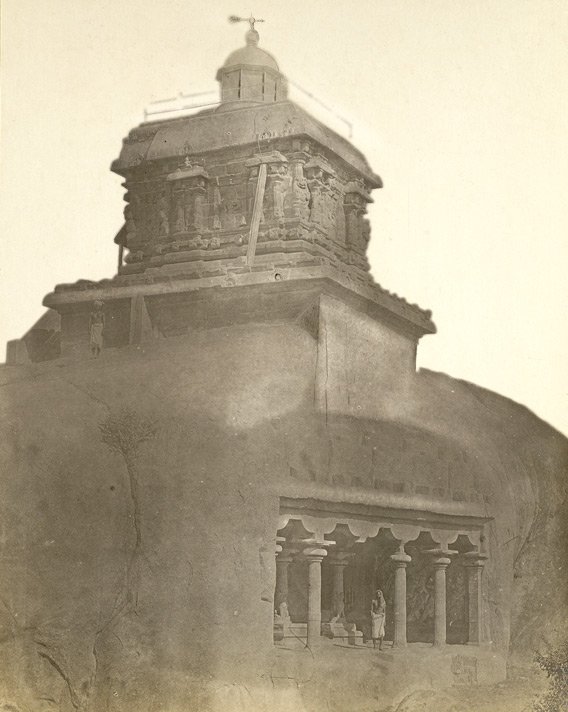

from the 1900-1901 Archaeological Survey of India; a rare image from the short period when the lighthouse was atop the temple

Alexander Rea, 1885

The Mahishasuramardhini Mandapa, also known as the Yamapuri temple, features three exquisitely carved reliefs on the cave walls of three sanctums. One is of Vishnu reclining on the seven-hooded serpent, Adishesha, another of Durga, the main deity of the cave temple Durga slaying the buffalo-headed demon Mahishasura, and the third sanctum has a sculpture of Shiva.

Its internal dimensions are 32 feet (9.8 m) in length, 15 feet (4.6 m) in width, and 12.5 feet (3.8 m) in height. There is frontal projection of the main central chamber when compared to the two chambers which flank it. On the front façade of the cave are 10 unfinished kudus. The cornice also depicts carvings of five gable-roofed semi-complete shrines. The façade has four carved pillars and two pilasters at the ends. The central chamber is fronted by a small mukhamandapa (entrance porch), which has two carved pillars with lion bases.

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

The central chamber entrance depicts guardians (dwarapalas) on the flanks. The back wall of the central chamber features a Somaskanda panel carved with images of Shiva and his consort Parvathi in their regal dress, each wearing a crown known as kirita-mukuta and other ornamentation, with their son Skanda seated between them. This panel also shows the carving of Nandi (bull), Shiva's mount (Vahana). Chandeshvara Nayanar, an ardent devotee of Shiva, is carved to the left of the carved images of the trinity gods Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu, who are shown standing behind the main image of Shiva and Parvathi. Brahma is carved with four heads and four hands, with the upper hands holding a water vessel and akshamala; the lower right hand is shown raised in an appreciative gesture to Shiva, while the left hand is in a kataka mudra. Vishnu's carving is also depicted with four hands; chakra and shankha are held in his upper hands, with the lower left hand showing a gesture of appreciation to Shiva, and the lower right hand held up in a kataka mudra. The image of Surya (Sun) is carved on the top part of the panel, between Brahma and Vishnu.

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

The north wall of the cave contains a relief depicting the battle scene of the two adversaries, the goddess Durga and the demon buffalo-headed Mahishasura. The carving is considered one of the best creations of the Pallava period. Durga appears with eight hands riding a fierce-looking lion. She is holding a khadga (sword), dhanush (bow), bana (arrows), ghanta (bell) in her four right hands; her four left hands display pasa, sankha, and dagger. An attendant holds a chatra (parasol) over Durga's head. She is in the battlefield with her army of female warriors and ganas (dwarfs). She is shown attacking, with arrows, the demon Mahisha, causing him to retreat with his followers. Mahishasura is armed with a gada (club). Mahishasura represents the forces of ignorance and chaos hidden by outer appearances. Durga is shown as a serene, calm, collected and graceful symbol of good as she pierces the heart and kills the scared, overwhelmed and outwitted Mahishasura. This is one of my favorite myths, because it’s so relevant to the manner in which everyday people are forced to defeat manipulative phonies in social and work settings, a quotidian war of good v. evil.

Manfred Sommer, 2015

A separate Brahma panel carving appears on the back wall of the left chamber, while the right chamber is repeated with a panel of Shiva that, according to the opinion of archaeologists, was originally meant to host a panel of Vishnu. One interpretation of this change is that the religious leaning of the Kings who ruled at that time changed from Vaishnavism to Shavisim. The Somaskanda panel in this cave is of a different architectural composition than similar panels carved in Dharmaraja Ratha, the Shore Temple, and the Atiranachanda Cave, supporting this notion. Archaeologists suggest the panel here was created during the reign of Rajasimha.

Manfred Sommer, 2015

On the southern face of the cave, there is a panel of Maha Vishnu in an Anantasayana mudra, (a reclining posture), lying on the bed of a serpent. He is shown with two hands, one is patting the coil of the Thousand-headed serpent known as Adisesha, and the other hand holds a lotus. Madhu-Kaitabha, the twin demons, are carved near Vishnu's feet in an attacking mode, armed with a Gada (mace). The demons are in a position of retreat, as Adisesha hisses at them with flames emerging from its hoods attacking them. Vishnu, who is unconcerned, is patting Adisesha to pacify him. Also shown in the panel are two ganas (dwarfs). The dwarves are Vishnu's ayudhapurushas (his personified weapons); the male gana is known as Shanka, and the female gana is Vishnu's gada. The other scene in the panel, is at its lower end, where three figures; his chakra (discus) in ayudha-purusha form, Khadga (Vishnu's sword) on the right and the female figure is Bhudevi.

practice panel for Arjuna’s penance, Alexander Rea 1885

Timothy A. Gonsalves, September 2022

The lighthouse, built in 1904, offers panoramic views of the town and aerial views of some of the hilltop temples. Between the 1880s and 1904, the light was actually installed on a new roof built over the Olakkannesvara temple, which was later removed. You must buy a separate ticket; it’s not included in the ticket required to visit the temples. There’s a woman with a whistle who’s supposed to make sure 20 people visit the top and come back at designated times, and she does a terrible job, creating a somewhat unsafe situation. The stairs are terminally clogged with people too scared to keep going up at more than a snail’s pace, who refuse to give any room for people to try to get down. There’s no understanding that people going up need to do so against the rail, and people coming down need to do so against the wall.

The outside walkway is narrow and equally ungoverned. Everyone clogs at the door, trying to get their perfect overhead shot of the temple hill, and takes way too long doing so chatting on Facebook Live or whatever when they should be recording a ten-second video and moving along. The walkway is too narrow for two people, yet people squeeze past each other back and forth in whichever direction; there’s no understanding that everyone will get their pictures faster if they slowly circle the top in one direction. Parents carry infants and toddlers upstairs and outside in their arms despite the guard rail being only waist-high, and people with huge cameras jostle with them dangerously. The worst part is, the view is nothing to write home about. People calling it the ‘view of a lifetime’ in their reviews just haven’t traveled much. The view of the Olakkannesvara temple is no better from the top of the lighthouse than from the rock the lighthouse is standing on, and the town and beach are unimpressive, even from above.

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Colin MacKenzie, 1816

The Krishna mandapa was originally an open-air bas-relief; the temple was built around it in the 16th century by Vijayanagar rulers. The sculpture shows Krishna lifting the Govardhana Hill to protect the cowherds and gopis (milk maids) from heavy rains and floods, very apropos for the Mahabalipuram hill site. The sculpture also seems to have been touched up and added to when the temple was built around it. The building faces east and has a length of 29 feet (8.8 m) and height of 12 feet (3.7 m).

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

Manfred Sommer, 2015

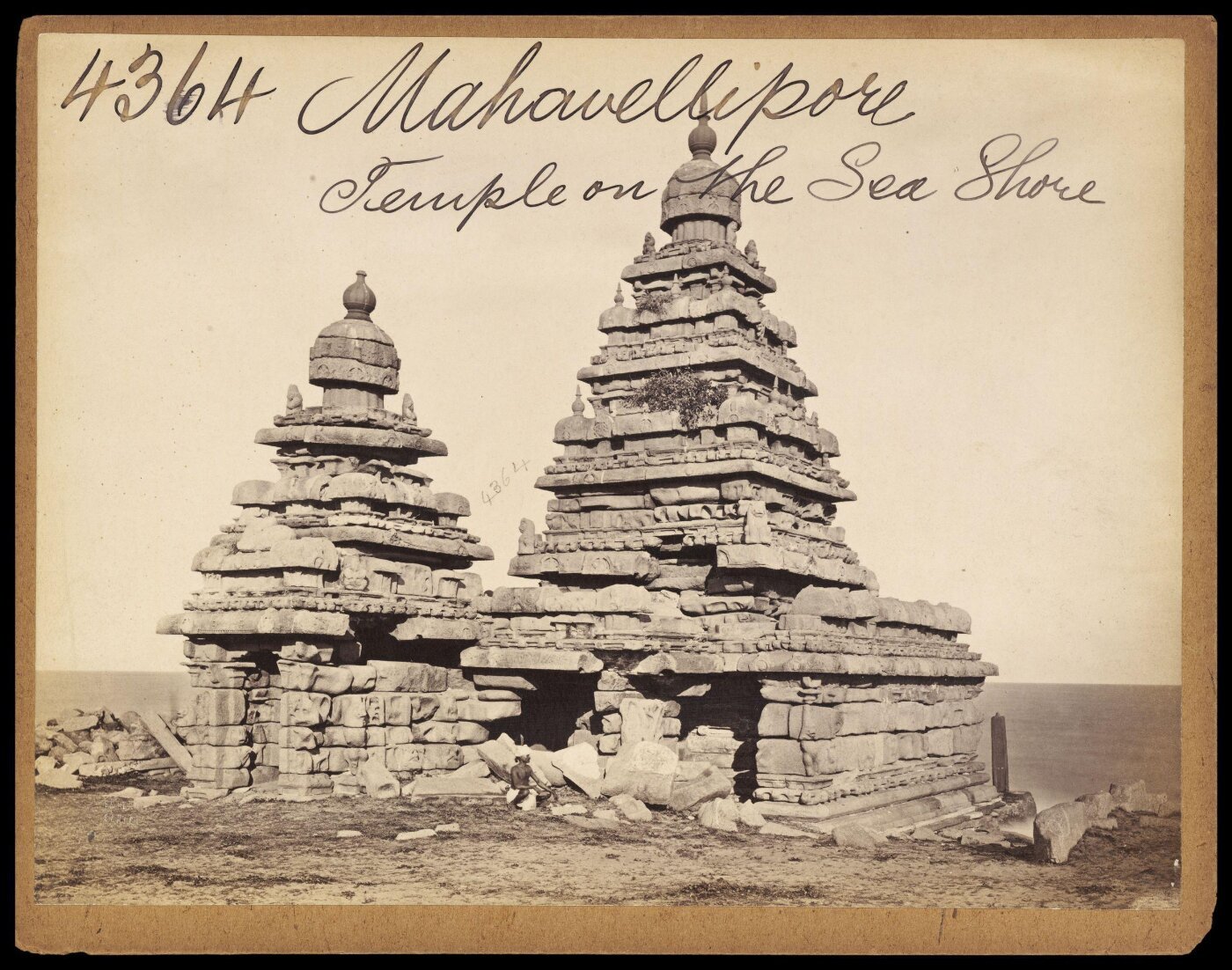

Colin MacKenzie, 1784

George Chinnery, 1802

John Gantz, 1825

plate 18 from James Fergusson's 'Ancient Architecture in Hindoostan,’ Thomas Dibdin, 1847

Francis Frith, c. 1860

probably Linnaeus Tripe, c. 1860

Alexander Rea c. 1880

Alexander Rea, 1885

The Shore Temple, dating from the first quarter of the 8th century, is newer than the rock-cut temples, but still among the oldest structural temples in southern India. According to local legend, the god Indra became jealous of ancient Mahabalipuram, a city of seven pagodas, and sank it during a great storm, leaving only the Shore Temple above water. There has been much debate over whether this local legend accounts for the old European name for Mahabalipuram of ‘Seven Pagodas,’ first used by Marco Polo and then by various medieval travelers after him. It’s unclear whether their accounts refer literally to seven temples they saw, or if they were just using a customary placename; it is clear they considered at least the Shore Temple an important landmark for sailors, and that at one point it was capped with something copper that flashed enough to be easy for them to spot.

After the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, the coastline was permanently altered, uncovering a large stone lion. Curious about whether the lion was a clue to the lost six pagodas, the Archaeological Survey of India started exploring the coastline using sonar. They found remains of two structural temples, one much larger than the existing Shore Temple, and one cave temple within 500 meters of the shore; they also found a 70-meter-long, 6-foot-high, wall. The most interesting clue, however, came from a large inscribed stone the waves uncovered. The inscription stated that King Krishna III had paid for the keeping of an eternal flame at a particular temple. Archaeologists began digging in the vicinity of the stone, and quickly found the structure of another Pallava temple. They also found many coins and items that would have been used in ancient Hindu religious ceremonies. While excavating this Pallava-era temple, archaeologists also uncovered the foundations of a Tamil Sangam-period temple, dating back approximately 2000 years.

Most archaeologists working on the site now believe that two historic tsunamis obscured the legendary “Seven Pagodas.” The first struck sometime between the Tamil Sangam and Pallava periods, destroying the Tamil-Sangam temple; widespread layers of seashells and other ocean debris support this theory. The second struck sometime in the 13th century and destroyed the Pallava temples. ASI scientist G. Thirumoorthy told the BBC that physical evidence of a 13th-century tsunami can be found along nearly the entire length of India's East Coast. If this is true, Marco Polo and his companions may have been the last Europeans to actually see the ‘Seven Pagodas’ before they passed into legend.

One truly unique element of the temple is the Bhuvaraha image in a well-type enclosure. The shikhara is erected on a circular griva, which has kudus and maha-nasikas on its four sides, each nasika an image of Ganesh. The kalasa above the shikara is missing. The carving of the Bhuvaraha depicts Varaha as the boar incarnation of Vishnu. This image is unlike Varaha depictions in other regions of the country, as there is no Bhudevi shown nor an ocean. The depiction is in the form of Varaha performing a diving act into the ocean to rescue Bhudevi. The sculpture only makes sense when the well is full; it’s unclear whether it was manually filled or meant only to manifest its myth when the temple was submerged in water during a storm.

As it stands today, all three temples of the Shore Temple complex are built on the same platform. The main Shore Temple, which faces east so that the sun rays shine on the main deity of Shiva Linga in the shrine, is a five-tier pyramidal structure 60 feet (18 m) high, sitting on a 50 square foot (15 square meter) platform. There is a small temple in front, which was the original porch.

The temple is a combination of three shrines. The main shrine is dedicated to Shiva, as is the smaller second shrine. A small third shrine, between the two, is dedicated to a reclining Vishnu and may have had water channelled into the temple, entering the Vishnu shrine. The entrance is through a transverse barrel vault gopuram. The outer wall of the shrine to Vishnu and the inner side of the boundary wall are extensively sculptured and topped by large sculptures of Nandi. The temple's outer walls are divided by pilasters into bays, the lower part being carved into a series of rearing lions. The temple walls are surrounded by sculptures of Nandi.

I had some problem or another both times I visited Mahabalipuram- first I got there too late and didn’t want to climb around in the dark; next I forgot my sunscreen and left my umbrella in the lighthouse and had to finally call it quits when I knew for sure I’d be burnt as a lobster the next day. I do plan on returning to the area at some point if only to go shopping in Kanchipuram; Mahabalipuram and Kanchipuram are about equidistant from Chennai airport, so one fine day if I return I will actually check out the Tiger Cave and the inside of the Shore Temple, and go to the sculpture museum. I’ll update this post if I do!

Shopping in Siem Reap, Part 2: Couture & Heritage Textiles | Siem Reap, Cambodia

There are three places worth shopping in Siem Reap, but they will cost an arm and a leg (and another arm, thanks) and are only for fabric aficionados: Samatoa Lotus Farm, IKTT, and Golden Silk Pheach.

Samatoa Lotus Farm

For $35 (or sometimes $50? I think they undercharged me) you can take a tour of the Samatoa Lotus Farm and factory. They make lotus silk, one of the most expensive fabrics in the world. It is harvested by hand from lotus stalks, filament by filament.

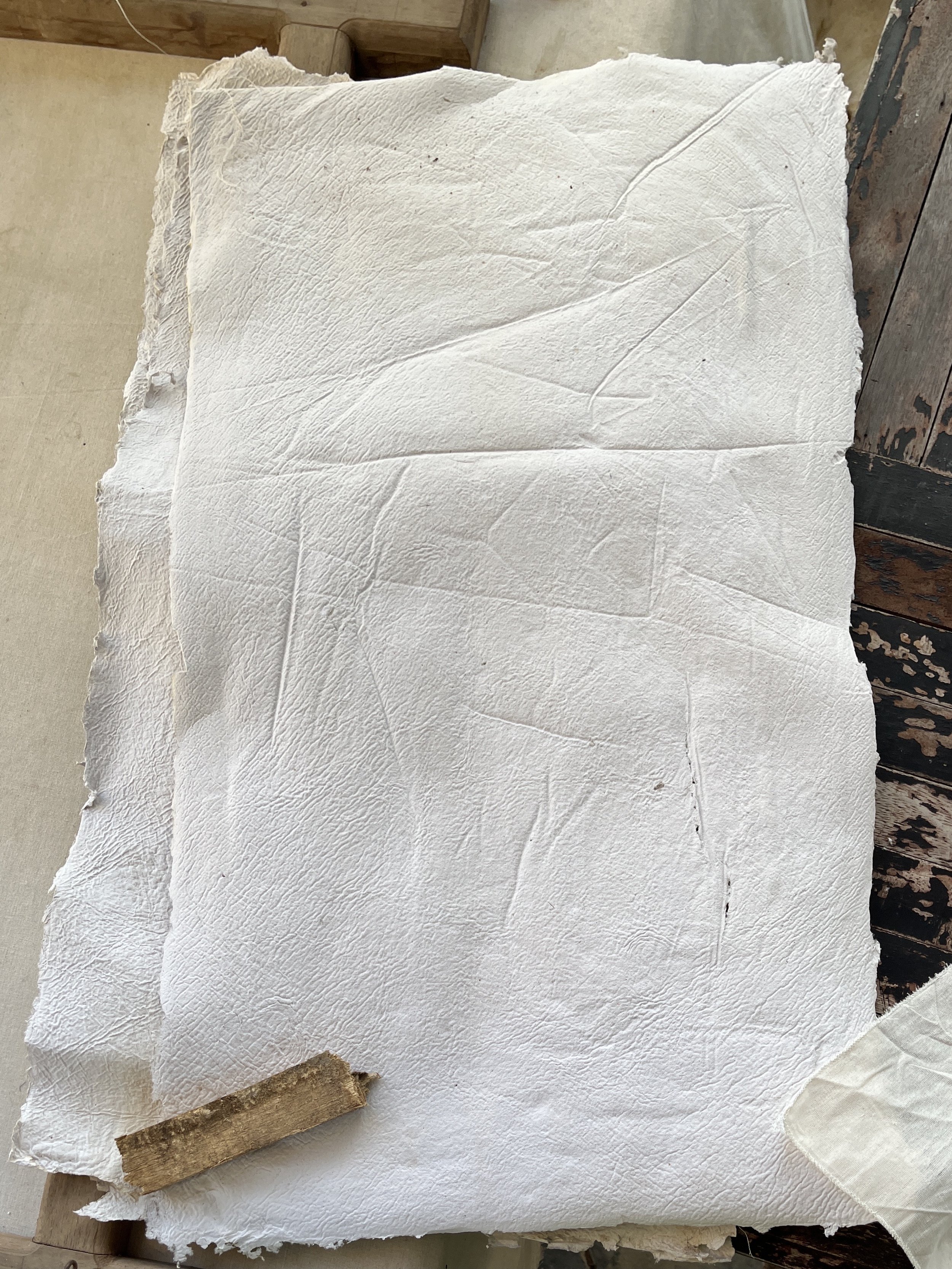

First, the owner explains why lotus silk is special- it's incredibly absorbent and naturally antimicrobial, plus completely sustainable. You also learn about kapok fruit fabric and some natural dye options. During your craft portion, you break apart lotus stems and twist the wet filaments to make a buddhist thread-style candle, make a sort of rough paper from lotus pulp, make old-fashioned incense sticks, drink lotus tea, and string dried lotus seeds on a lotus silk yarn to make a bracelet. At sunset, you take a short motorbike ride to an absolutely impoverished little village on a lotus lake, where they take you out on a boat and you can take pictures of the beautiful flowers, and eat some fresh lotus seeds. It's a fantastic experience and excellent value.

It takes 3 weeks to harvest enough thread to make a single scarf, which then takes 9 days to weave. It’s a 100% ethical and sustainable business, with environmentally safe and renewable production and fairly paid workers. So, the goods they sell in their shop are inevitably somewhat expensive by today’s standards, where terrible human and environmental tolls are the norm in the fashion industry. Most products are simple, some exquisite, some (especially their vegan leather efforts) a bit ugly and experimental. Hairbands run around $60, belts $75, face masks $45. Their UNESCO prize winning scarf in a 50/50 silk/lotus silk blend is $400, a bucket hat $450.

I knew I wasn't buying immediately, so I didn't dare ask the price per meter for anything, but you can get a quote on their website. 6 or 7 meters of fabric in their UNESCO blend is on my wishlist for when I’ve saved something near what I think they’ll ask. Buying from businesses like this is the definition of putting your money where your mouth is!

If you want to visit, you absolutely must arrange with a tuktuk to take you there, wait for you, and take you back to your hotel. It is in the middle of nowhere (a solid 40 minute drive outside of Siem Reap proper), Grab doesn't work out there, there's no spot on the road to hail a motorbike or tuktuk, and locals get rowdy and drunk as soon as the sun goes down (especially the tuktuk and moto drivers!); you absolutely will get stranded in an unsafe situation if you don't have your own transport. Still worth the visit!

IKTT

You can visit the shop, or get the full experience and arrange via their website to visit the village and stay overnight there.

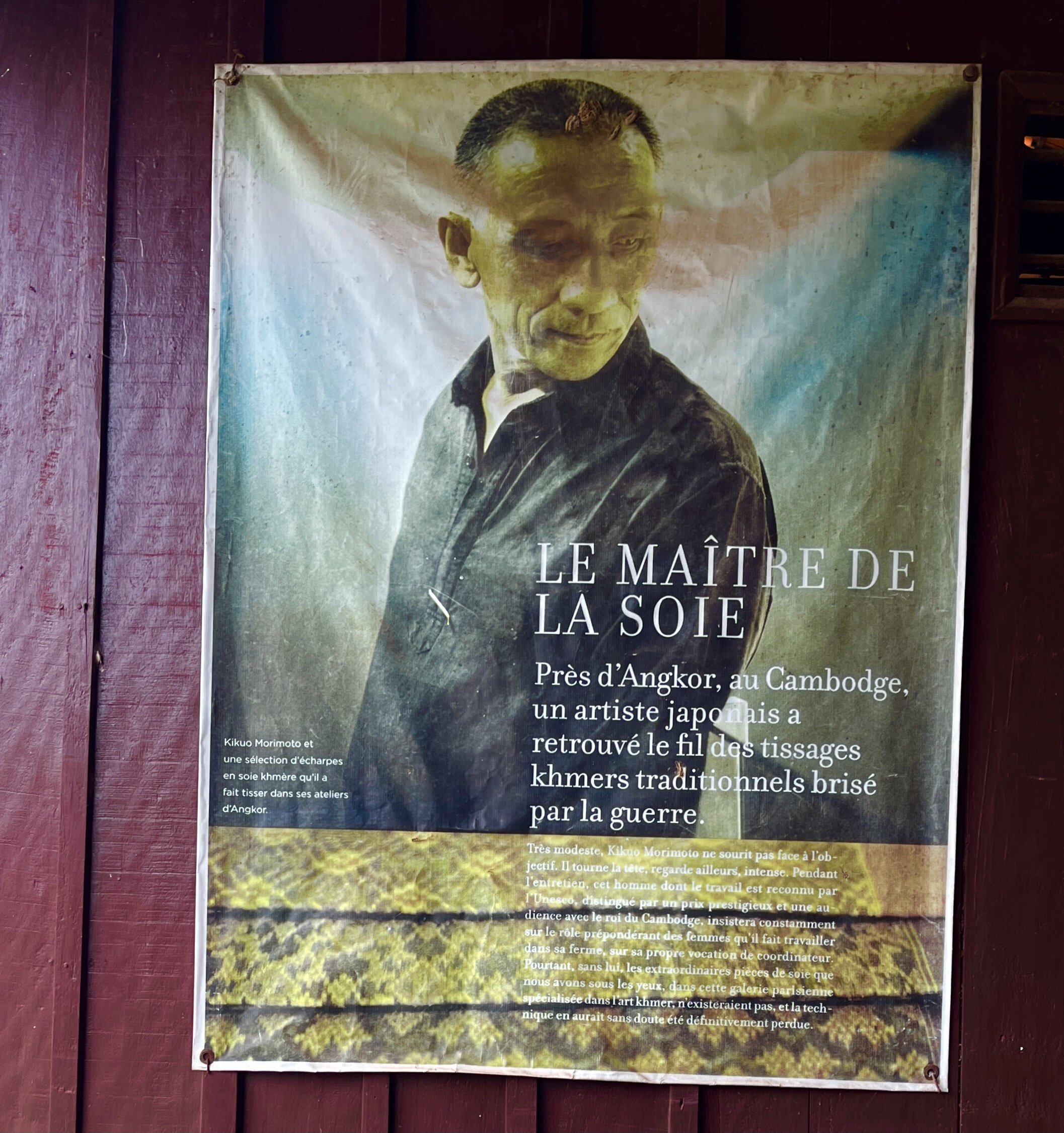

To quote the IKTT website: "The IKTT specialises in the revival of Khmer silk ikat. Throughout history Khmer silk weaving has been regarded among the best in the world, however, after years of war, this ancient art form nearly vanished. The beauty of such silk has been its savior. Founded in 1996 by Kikuo Morimoto, we take a purist approach to the reproduction of traditional textiles, not just by recreating the style but by following the traditional practice seen a thousand years ago in the ancient times of the Angkor Dynasty. To achieve this, we have re-planted a traditional forest to cultivate everything from the natural dyes to the silk in a rich natural environment."

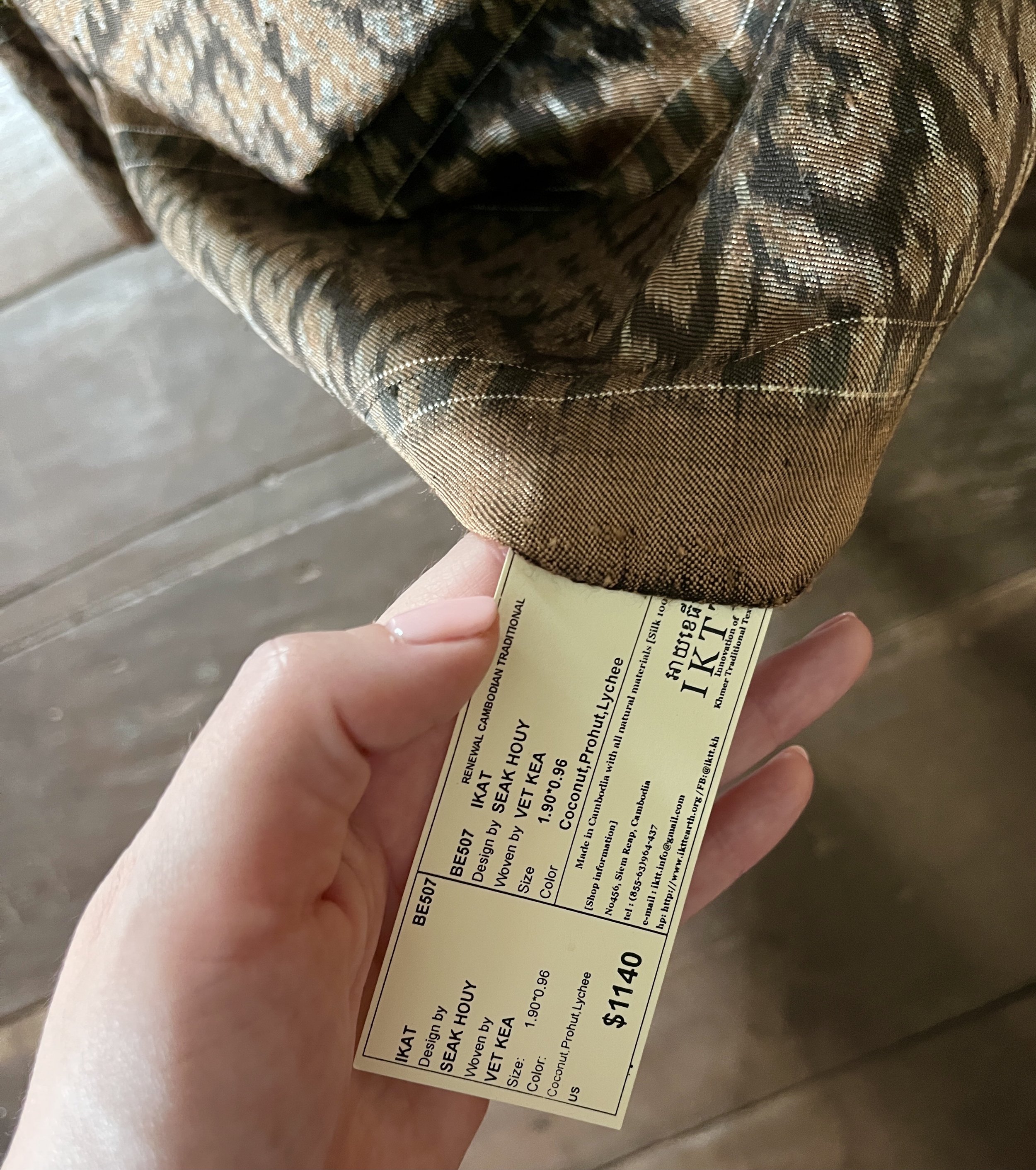

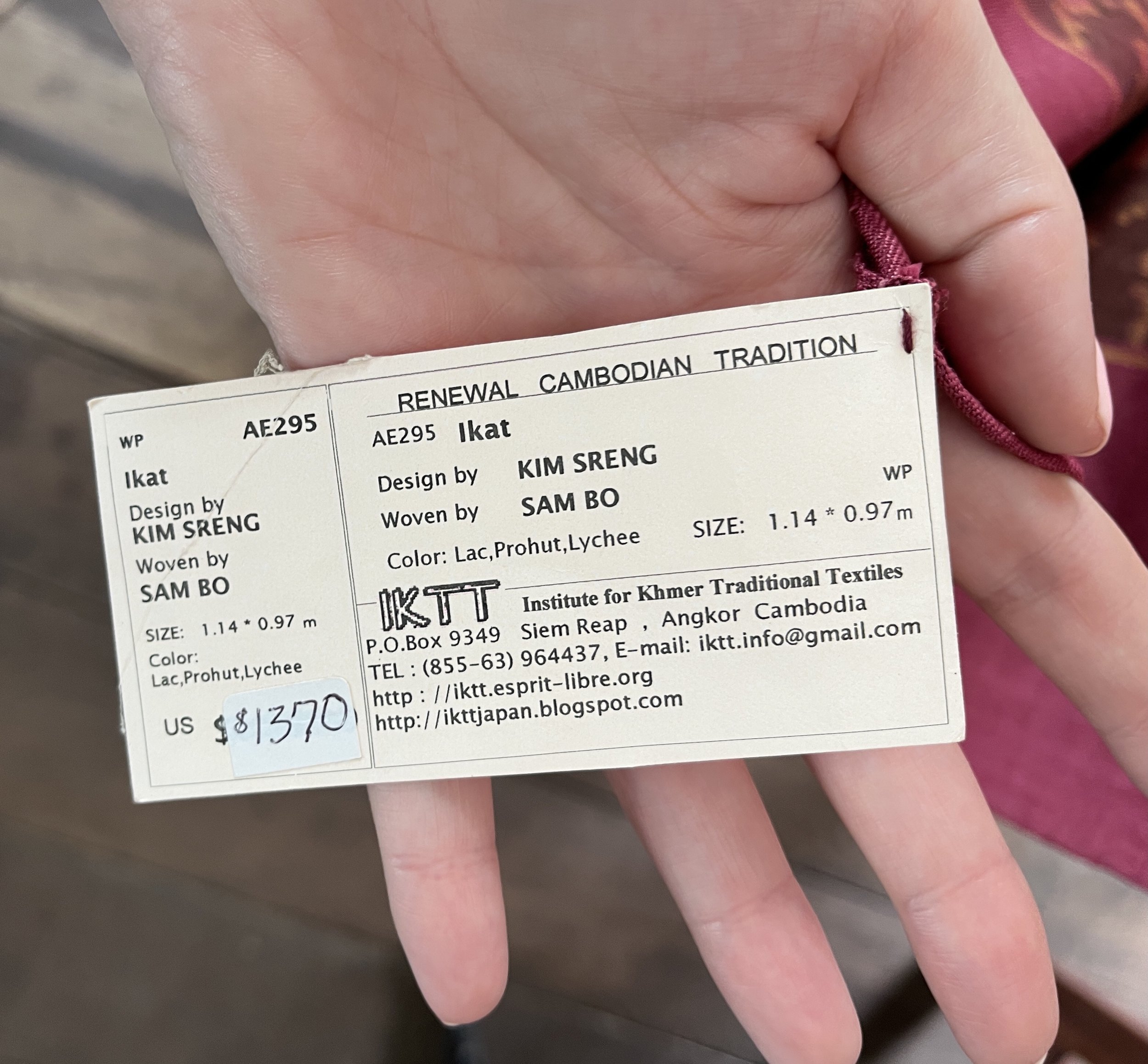

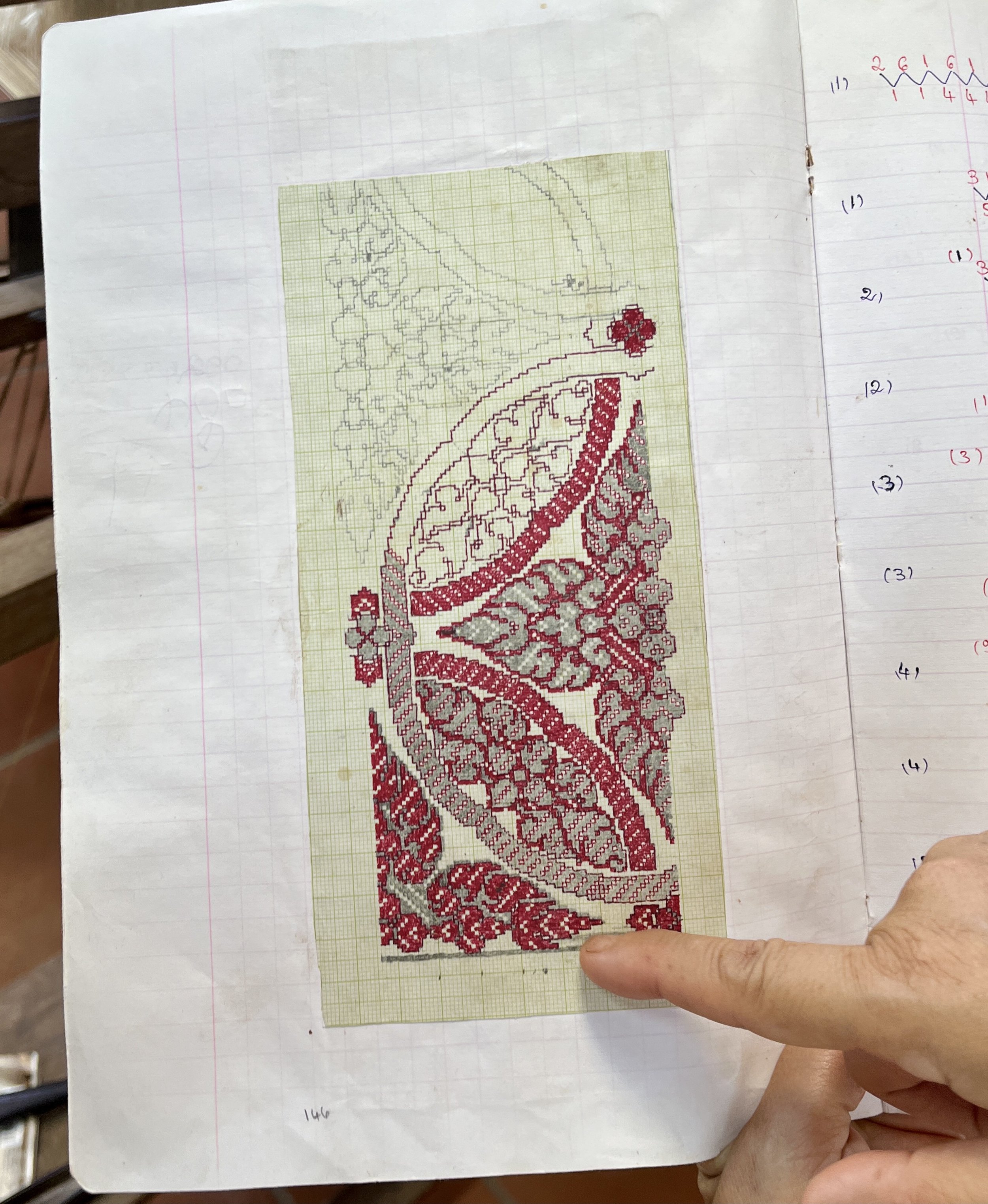

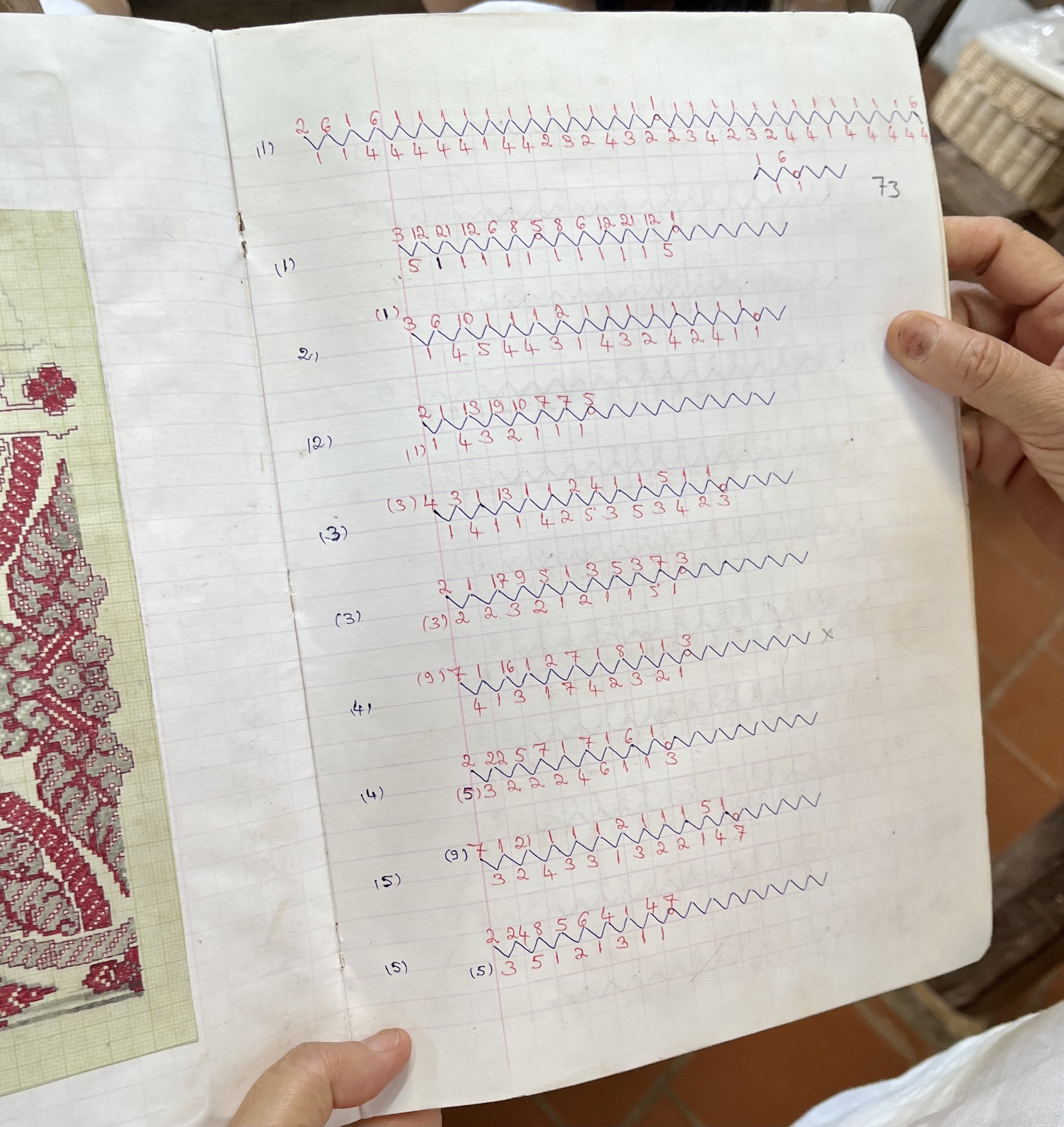

The 'purist approach' is three-pronged: Cambodian golden silk worms; natural dyes from local plants; and hand spinning, tying for ikat, and weaving. Everything is done to the highest traditional standards; they offer some souvenir items like kerchiefs and shawls in solids or non-traditional oversized gingham, but every pidan (religious wall hanging) and sampot hol (women's ikat skirt) is traditional in every respect. They have their own mulberry tree forest and their own lac insect nests, prohut trees, almond trees, lychee trees, annato plants and wild Cambodian indigo plants to make their own dyes; around 160 people (those working in production and their families) live in their own old-fashioned weaving village; they use the dye techniques and around 200 weaving patterns handed down from their ancestors. I think one of the best things about shopping at IKTT is seeing the year your piece was made, the natural plant dyes used, and the weaver. You truly buy an heirloom, not just a skirt or a scarf. Being perfectly historic, all production is 100% organic and sustainable.

They seem to financially support themselves primarily through a Japanese clientele and network cultivated over 20+ years by their founder, but they do have a shop in Siem Reap and a strong instagram presence. Sampot hols are available at the shop, or by custom order; it takes 2-3 months for a sampot hol or pidan to be made, perhaps more depending on the season and intricacy. A traditional size Cambodian sampot hol is around 2 meters by 1 meter, perhaps a bit smaller; Cambodian women are quite small. A heavier woman can order an extra long version to ensure sufficient drape, but due to the dimensions of the traditional looms no skirt will be full length, or even ankle length, on anyone over 5'5" or so. Midori, the contact person, responds very quickly to any inquiry and will quote a price per meter for a design. For one of the traditional sampol hols, expect to pay around $600/meter. A complicated pidan will be more; a solid or simple stripe less. That breaks down to between $1000 and $2000 per skirt depending on the dyes, weave, size, time etc.

Golden Silk Pheach

Finally, there is Golden Silk Pheach. A Cambodian raised in France, Pheach's trajectory since returning to Cambodia has been much like the founder of IKTT's: she bought a small farm, planted mulberry trees, feeds them to indigienous Cambodian golden silk worms only, grows and buys local natural dyes only, and employs and trains local women in traditional techniques. The main difference is that while IKTT is primarily interested in providing historically accurate products, Pheach has a very refined aesthetic, and is able to use traditional techniques to create modern products that recall their traditional origins in the most elegant way.

A tour at Golden Silk is like a personal couture appointment with Pheach: she explains the history of Cambodian golden silk weaving since Angkorian times, and how the rare Cambodian golden silk worms are superior to the genetically modified white silkworms used elsewhere in the world. She also explains not only how ikat dying works, but where she gets her inspiration for her modern designs, and how they build custom looms for large textiles.

A small scarf at the shop is around $500; the larger and more intricate they get, they climb over $1000, $2000, etc. Some of the largest, most difficult designs can only be executed by an artisan with many years of experience, who then requires another 2 to 3 years of full-time work just to complete the piece.

Two Sunsets in Songkhla | Songkhla, Thailand

I can’t recommend Samila beach! It’s sharp underfoot, crawling with university students and their trash, stray dogs and their shit, and the accompanying flies of course. The far end has no mobile service; you have to walk at least a kilometre to a 7-11 to call a grab. The colors of the sunset were something like a Titian, and it’s still a no from me.

I enjoyed the sunset much more from Café Der See Nakkornnok, my go-to restaurant in the old town. They have a great deck out back and occasional dinnertime live music from a chill guitarist/singer. He sings some unexpected western classics, like Louis Armstrong and Nina Simone, but I really enjoyed when he played a couple songs written by the late king. As for food, I liked the scallops, but their softshell crab is my favorite. They also serve some imported beers, overpriced but welcome in a town where you can’t buy alcohol in the supermarkets or convenience stores.

The City Pillar Shrine | Songkhla, Thailand

The Songkhla City Shrine was built in 1842, during the lifetime of the founder of Songkhla's hereditary ruling family, Phraya Vichian Siri (Tianseng Na Songkhla). Inside, there once was a city pillar made from Javanese cassia wood. Unlike most Thai city pillars, which are large stone or brick and plaster monuments, this city pillar, though no longer wooden, is still small and kept indoors. The first city pillar was given by the Thai King Nangklao in 1842, along with offerings given as alms to Phraya Songkhla (Tianseng) to establish the shrine.

At that time, the king also selected Phra Udom Pidok as the leader of Buddhist ceremony and Phra Kru Assasachan Phram as the leader of Hindu ceremony, and each was accompanied by eight worshippers in their faith. Phraya Songkhla (Tianseng) built four ceremony halls facing each cardinal direction, and arranged a large parade of Thai and Chinese Buddhists to carry the pillar and the candle to the new shrine.

At the sacred time (as determined by astrologers), the 10th day of waxing moon in the 4th month, in the year of tiger, 1204th year of Thai minor era at 7.10 a.m. (or 10 March 1842), the Buddhist procession met the awaiting Phraya Songkhla (Tianseng), along with Phra Khru Assadachan and the Hindu priests, who placed the pillar at the center of Songkhla town. After the pillar was erected, a party was held for 5 days and 5 nights. Phraya Songkhla (Tianseng) endowed the temple with 22 monks he personally supported.

At the time, the temple complex included a Khon performing hall, a puppet performing hall, a Chinese opera performing hall, and 4 Norah performing halls. Later, Phraya Songkhla also built 3 Chinese-style buildings to cover the pillar and a shrine of Chao Sua Muang.

In 1917, in the era of King Vajiravudh, Prince Yugala Dighambara, the viceroy of southern region, published an announcement that the pillar was rotten by termites. Local people and merchants in Songkhla raised funds to rebuild the pillar out of cement, and consecrated it on 1 March 1917, the 7th day of the waning moon in the 4th month, 22 minutes and 36 seconds before noon. Four astrologers stood at each cardinal direction began by placing soil from the far reaches of the province into the foundation, and workers were done erecting the pillar by 8.41.36 that evening.

Today, the Chinese opera hall is still in use but the others have been turned into school buildings. The temple is at the north end of the main Chinatown strip, so not a bad place to start exploring old town Songkhla (which should only take a day or two max).

An Afternoon in Hat Yai | Hat Yai, Thailand

The closest airport to Songkhla is Hat Yai international, which has a surprising amount of junk food and insufficient places to charge a cell phone. The announcements are truly constant, irrationally repetitive; it’s loud, busy and unbearable. Vietjet wouldn’t let me check my suitcase early, a necessity to get past security and into a business lounge, so instead I paid a nominal amount (I think 30 baht? Maybe 50?) to leave my suitcase in the luggage room and hit Hat Yai town.

Founded in 1928, there’s really nothing of historic importance in Hat Yai. Until perhaps 10 years ago there were only two hotels in town, the cheap Mandarin and the expensive Lee Gardens, which was the site of a car bomb attack in the continuing ant-Thai Muslim terrorism in the area. The town can be seen in an afternoon, so the first place I checked out was the oldest Chinese restaurant in town, Nai Roo, which came highly recommended. I had two of their most famous dishes, black pepper seafood and abalone. Honestly? The black pepper seafood was just OK and the abalone was less than OK. The quality was the same or lower than any cheap Chinese takeout place in New York. I think Hat Yai is small enough that this is the closest thing they have to a foodie/heritage type restaurant, but it’s definitely not worth going out of your way for.

Next, I headed over to picturesque Wat Chue Chang, a very big, very new place. Again, just . . . whatever. It’s fine for a photo I guess, or to get out of the sun. My last couple hours I spent at Lorem Ipsum café, the local LGBT coffee shop. It’s located on one of the two blocks in Hat Yai that actually dates back to the 1930s, so I took some photos of the old fashioned buildings and actually read the entire lorem ipsum passage by Cicero, conveniently printed on the cup. I attempted and failed to engage the staff, who had no idea who Cicero was or what the passage meant or its significnce in graphic design. Exciting times, I tell you!

Hat Yai: not worth visiting but better than sitting in the airport if you can spare the approximately $15 for round trip cab fare (250 baht from the airport to Nai Roo via airport taxi, 160 baht from Lorem Ipsum back to the airport via grab).

Wat Keseraram | Siem Reap, Cambodia

In Southeast Asia, I’m reminded all the time that dying for politics is dying for nothing. At Wat Keseram (some locals use the extra ‘ra’, others don’t; no one knows what’s right) I’m reminded again.

Built in the early 1970s as a well-equipped modern Buddhist temple and school, it has the largest collection of Buddhist folk paintings, finest woodwork, and loftiest hall among Siem Reap’s modern temples. Almost as soon as it opened, Pol Pot came to power and all religious worship was prohibited, all education banned.

Until 1979, old and senior monks were killed immediately, while young monks were forced into marriage or the military (any who resisted were also killed). Out of approximately 66,000 monks living at 4000 temples before the Khmer Rouge came to power, the regime claimed to have executed 26,000 by 1989, with a further 25,000 dying from starvation, exposure, overwork and illness during forced labor. The killing putatively stopped in 1979, but most monks were unable to return to their monasteries for another decade or more.

When monks returned to the Pagoda of Cornflower Petals, they found something disturbing: their school had been razed and replaced with a torture chamber. Even more disturbing, whenever they broke ground for a new stupa, they found bones of the tortured and executed were already there. For decades, they collected bones in a rough wooden spirit house, but by 2015 they had enough money to build a proud cement stupa.

Today, Wat Keseram is a busy meditation center and very active temple, and uses donations beyond what is necessary to maintain the monks to feed the pets abandoned here by those who can’t afford them.

Shopping in Siem Reap, Part 1: Some Good, but Mostly Bad and Ugly | Siem Reap, Cambodia

In this post, I'm going to deal with the unfortunate reality of shopping in Siem Reap. In my next post, I'll cover shops of excellence, so stay tuned.

First things first, Psaar Chaa, the old French covered market. It’s Chinese trash and tourist tat on one side, a wet market on the other. On the surrounding streets are some little souvenir shops and restaurants, but nothing good or interesting or old.

Before we get to the good stuff, let me warn you about the number one shopping scam in Siem Reap: Indian immigrant boutique owners selling mass-produced Indian junk as Cambodian handiwork and antiques to tourists, at a ridiculous markup to boot. To add insult to injury, they name their stores things like 'Cambodian Cottage Industries' and 'Asian Arts Emporium' (both real places and perfect examples of this scam) to lure in naïve Westerners. They typically get your business by running a deal with tuk-tuk drivers and hotel owners; if you tell either to direct you to a silk or silver shop, they bring you to these places instead and abandon you there (typically a tuk-tuk will ask to wait for you and get the return fare, not drop and run). They get paid either by the number of tourists dropped off, or on a commission basis if you buy something. The Indian salesmen are smarmy and will tell you any lie you could dream up, 'help' you try on the merchandise, and offer dumb discounts again and again, making it not only very socially awkward but often physically difficult to leave their shops. Not only is factory fresh questionable metal actually “antique pure silver” according to these scammers, but machine embroidered polyester is “hand embroidered silk”, or even “lotus silk”, etc. I've seen scarves selling in these shops for $56 that are sold for $8 before bargaining in Ho Chi Minh City street stalls (or $1.50 each, if you're willing to order 40+ of them from AliExpress yourself). One boutique quoted me $750!! for the same super low grade semiprecious stone and likely-not-silver necklace I was quoted $140 for at the "Afghan" stall in Bangkok's Chatuchak market, and I’m sure I could have actually bought for $70 or less. These guys have the fanciest shops and speak the best English in town, and charge high prices, so perhaps some Westerners believe they have the best quality merchandise as well; they certainly do not. Indian restaurants in Siem Reap? Go for it, 100%. Indian purveyors of Cambodian goods? Run away, literally.

$1256 usd ?!?!?!

Similarly terrible experiences are the two most popular old-school souvenir shops, Sam Orn and SK Hand Made Silver, just a block away from each other on Rue Jean Commile. At least they're Cambodian owned and sell Cambodian goods, but they also have tuk-tuk driver commission deals, and come with a SERIOUS caveat: If you don't want to bargain hard for a long time and/or you won't feel OK walking away at least once, don't bother. If you're not sure you can handle it, check out the google maps reviews for the sordid tales. They survive by scamming tourists, lying about their silver quality, telling you their first outrageous price on silk is already a 40% discount, etc. They are such shameless, consistent scammers that they make themselves extremely difficult to purchase from, actually. I've walked away from fabric I genuinely wanted several times because I simply did not have the time and energy for their shenanigans; if they had been reasonable from go they could have gotten a few hundred bucks off me. You must use common sense, especially with the silverware and jewelry: they tell you the silver is 980/1000 (almost pure silver) or 925/1000 (sterling), when it's just copper with silver alloy plating. The stones are cloudy, heated, and dyed, if they're real at all. The prices are ridiculous; I was quoted $1400 for a pair of "silver" and "ruby" earrings I'd never pay more than $200 for, $150 probably. Negotiate hard or don't buy at all. Same with the silk; it’s already hard to tell what’s Cambodian or just another Indian import, and they start outrageously high ($60 and $70 per meter), and it's up to you to get down to where it should be, $20 or $25.

The next step up is Hup Guan Street. Also called Kandal village (though it's two blocks long if that), it was the tiny little high street in the colonial era. It's still the chicest address in this one-horse town, and boutiques like Louise Loubatières and Garden of Desire sell to trendy tourists hoping to buy nice souvenirs rather than knickknacks. Quality is acceptable (real silk, cotton, raffia, etc.) but the products are mostly Alibaba junk from China and Vietnam marketed and priced as handmade local wares. Two examples I saw at Louise Loubatières were $60 for a Chinese linen button-down shirt that's $11 on the Aliexpress app, and $12 for a Vietnamese lacquered horn bangle that's $2. The shop across the street sells private labeled $7 and $9 Chinese factory-made seagrass purses for $160+, claiming they're using traditional Cambodian basketry materials and techniques in modern designs. I guess if you literally need clothes and $250 is nothing to you, buying from these boutiques is better than supporting H&M or Shein, but it's certainly not what you’d hoped for when you arrived on Hup Guan. Hup Guan’s sole redeeming trait is a Mexican restaurant at the end of the street that sells sufficiently authentic food and great margaritas because the owner lived there awhile.

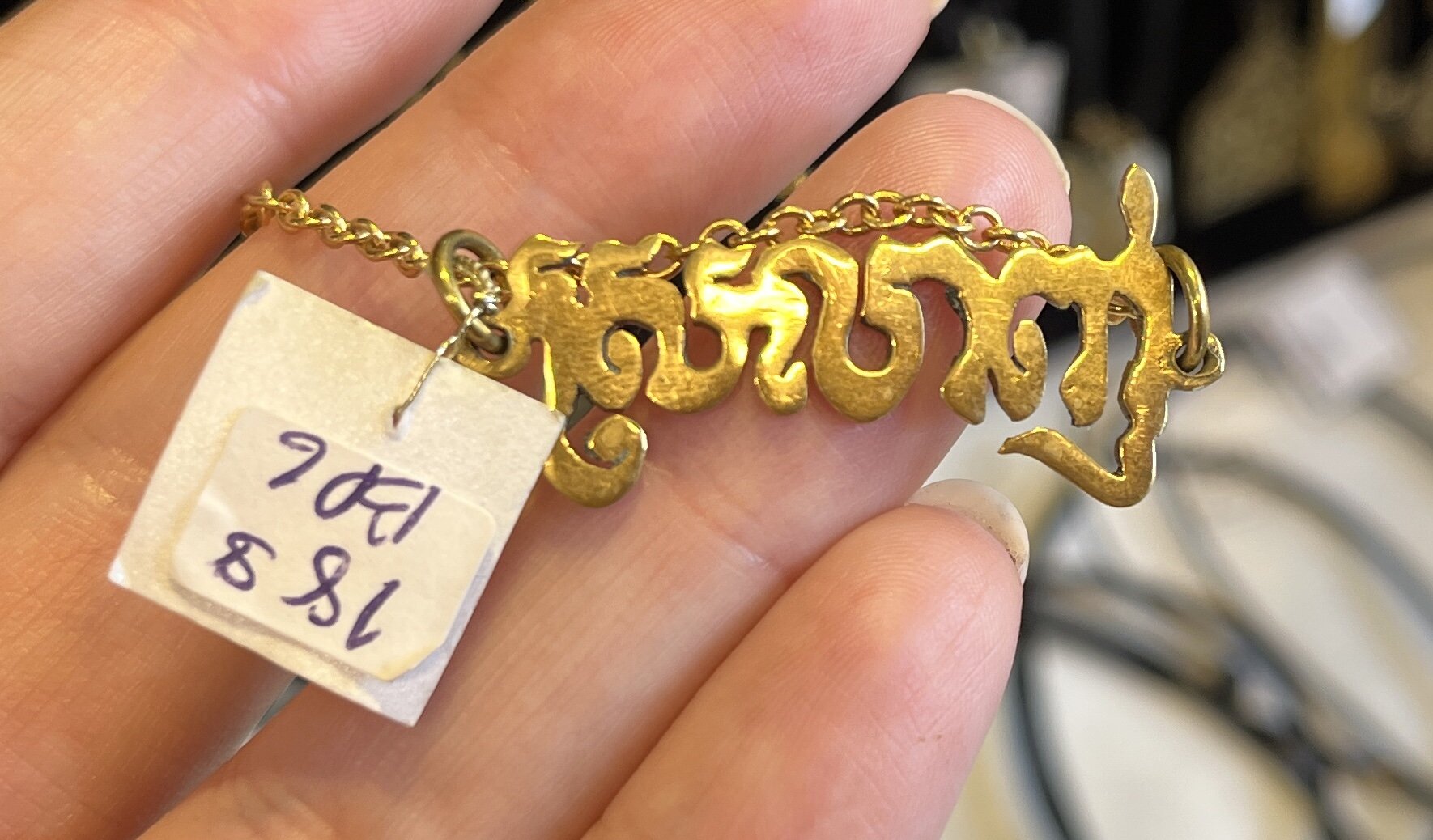

There are some similar AliExpress travesties at the Made in Cambodia outdoor market, but there are also genuine local products sold here. I feel bad for people selling authentic goods here because it's hard to separate the wheat from the chaff. Even among authentic goods, quality is take-it-or-leave-it. It's a very small market- perhaps 30 stalls, with nothing too exciting- the best of it is little notebooks with covers made of watercolors by local schoolchildren and teachers, jewelry made of nuts and seeds, local liquor and spices, and the typical ten million indigo scarves. Some sellers tag their products, others set their prices according to how rich they think you look, and they all charge in US dollars. I was quoted $60 and $90 respectively for two large necklaces made of seeds (wowzers, I know it takes time to make jewelry but you can rent an apartment within 10 minutes of Siem Reap proper for $150/month), $45 for a large handwoven undyed linen scarf, $25 for a brass nameplate necklace reading 'peace' or some such in Pali? Khmer? (presumably hand-tooled?) etc. The first two vendors when you walk in are landmine victims: a young man missing a leg, and a (supposedly) deaf woman. I think this place is the best option for reasonably priced Cambodian souvenirs, if you have a little luck and judgment. Again, there's no harm in taking a couple of photos, doing a little research on Alibaba, and coming back to purchase later.

The first place I'd even consider buying something is the Angkor National Museum gift shop. Regrettably, I don’t have pictures; they were following me rather aggressively and I felt awkward snapping without buying. As for merchandise, it’s completely mischosen. Of course there’s the standard 10,000 scarves, as if anyone needs another scarf. And who in the world is carrying home a foot-high bronze from a museum gift shop? Another thing that annoyed me immensely was their clutch bags. I was looking at them closely, hoping to buy because they seemed to be made of locally woven silk, but couldn’t because they were all wrong-sized and shapeless, barely padded envelopes with some awful fabric flower applied. Fashionable tourists don’t carry evening bags that look like lingerie bags or pillowcases with fake flowers attached. I was looking for a laptop case, an ipad case, a tissue case, packing cubes, anything remotely useful . . . nothing. Some of it is also imported nonsense meant to cater to Chinese tourists (jadeite and pearl jewelry?), which is tough because once you introduce foreign junk into the mix, how do I know I can find something locally and ethically sourced? Out of all the Southeast Asian tourist shops I’ve been in, I don’t believe I’ve ever seen evidence the merchandiser ever asked a single tourist what they wanted or needed, instead offering wares that are neither authentic to their culture nor matched to a tourist’s eye, but some terrible unsaleable compromise, and the Cambodian shops are no different. At least some of it seemed locally produced, and funds support the museum and local archaeological efforts, an undeniably good cause. What I would buy there is books! It's the only good bookshop in Siem Reap, with books on Angkor and Cambodia in English and French that just aren't available elsewhere, specialty books that are not on Amazon or in Kinokuniya etc.

The second place worth a dedicated shopping visit is Artisans Angkor. It's a standard tourist destination if you stay at one of the high-end resorts. I found their finished goods overpriced ($50 for a pair of espadrilles, $170 for a shapeless dress, etc.) but their fabric by the meter is worth looking at. They have their own silk farm; it's white silk made from originally Vietnamese worms and machine woven, so at the cheaper end of local, ethical production. Yet, the colors, weaves and patterns are distinctly Cambodian, different in style from Vietnamese, Thai and Chinese silks. Their prices by the meter are 25-50% cheaper than what you would pay in Europe or the Americas for equivalent quality fabric imported from China.

And that's where the middle market begins and ends in Siem Reap. The remaining three places worth buying from are couture fabric shops with prices at or above Hermès, literally. Check out Part 2 for details.

Southern Women's Museum | HCMC, Vietnam

The Southern Women's Museum is a no-go, in my opinion. It's made up of two buildings; as of 2023, the main building has been closed for construction for years and the annex is severely mold damaged and reeks, and I'm not sure if that's being addressed properly. The villa next door is also under very loud construction.

As for the content of the museum, it was incredibly, unexpectedly, one-sided, entirely focused on communist activists operating in Saigon and other Southern cities. It was also totally unconsidered; the tone was very much homage rather than historical examination. The artifacts were sparse.

You can visit in 20 minutes, but in my opinion you should only bother doing so if you happen to be within a 2-block radius; definitely don't make a special trip for this. If you want to visit a women’s museum in Vietnam, make time to see the museum in Hanoi.

Ho Chi Minh Port Museum (Nha Rong Dragon Wharf) | HCMC, Vietnam

Before I say anything about Ho Chi Minh, I'd like to issue a disclaimer: I find him fascinating as a person and possessing of many superior intellectual and moral attributes. I've read Ho Chi Minh Thought and the Revolutionary Path of Viet Nam by General Vo Nguyen Giap. I've been to his mausoleum, childhood home, revolutionary office, and a pile of other sites dedicated to him. That said, perhaps culturally, definitely personally, I can't abide the dear leader mentality, no matter to whom it's applied.

The Ho Chi Minh Port Museum (otherwise known as Nha Rong or the Dragon Wharf), is just another Ho Chi Minh museum, which you can find in any (and every) large or midsize city in Vietnam. It's got a few personal effects, a couple pamphlets, and seems to exist solely to inculcate schoolchildren. to my mind, it's a waste of a good building; on the other hand, at least crowding and overdevelopment has been staved off around it, which is more than can generally be expected in Saigon. the entire Ba Son port area, with umpteen untouched architecturally and historically significant 1880s and earlier French buildings, was sold to a residential property developer in 2015 to build more quote-unquote luxury highrises, so the Ho Chi Minh connection is indeed the sole reason the building survives at all.

The building itself dates from 1860, though the site has operated as a mercantile port since at least the 1610s. 45 nautical miles from the sea, the port was never able to effectively compete with Hong Kong, Singapore, and Jakarta, but was so well-established in terms of infrastructure and renown that the French decided not to bother moving it. From 1861 to 1901 the wharf was operated by Messageries Maritimes, and in June 1911 Ho Chi Minh doubtless processed through the building as a kitchen worker on a steamer destined for Marseille. The area has not been landfilled at all, so the shape of the river here looks the same as it does in photographs from 150 years ago. The view is nice, and the grounds are nice. It is not a must, in my opinion, but it is a quick visit.