Built in 1741, the old house of Tan Ky is a grand example of the traditional merchant houses of Hoi An, arising at the zenith of the town’s importance as a commercial port. It incorporates elements of traditional Vietnamese, Chinese, and Japanese wooden houses.

Japanese influence shows in the main roof of the front house, constructed in the triangular five rafter style, and the layout of connected small rooms that can either be shuttered or left open to form a larger space. The tubular townhouse design, with two story front and back houses, divided by a courtyard, and opening onto parallel streets, is uniquely Vietnamese. And of course, the whole place was constructed by local Kim Bong carpenters.

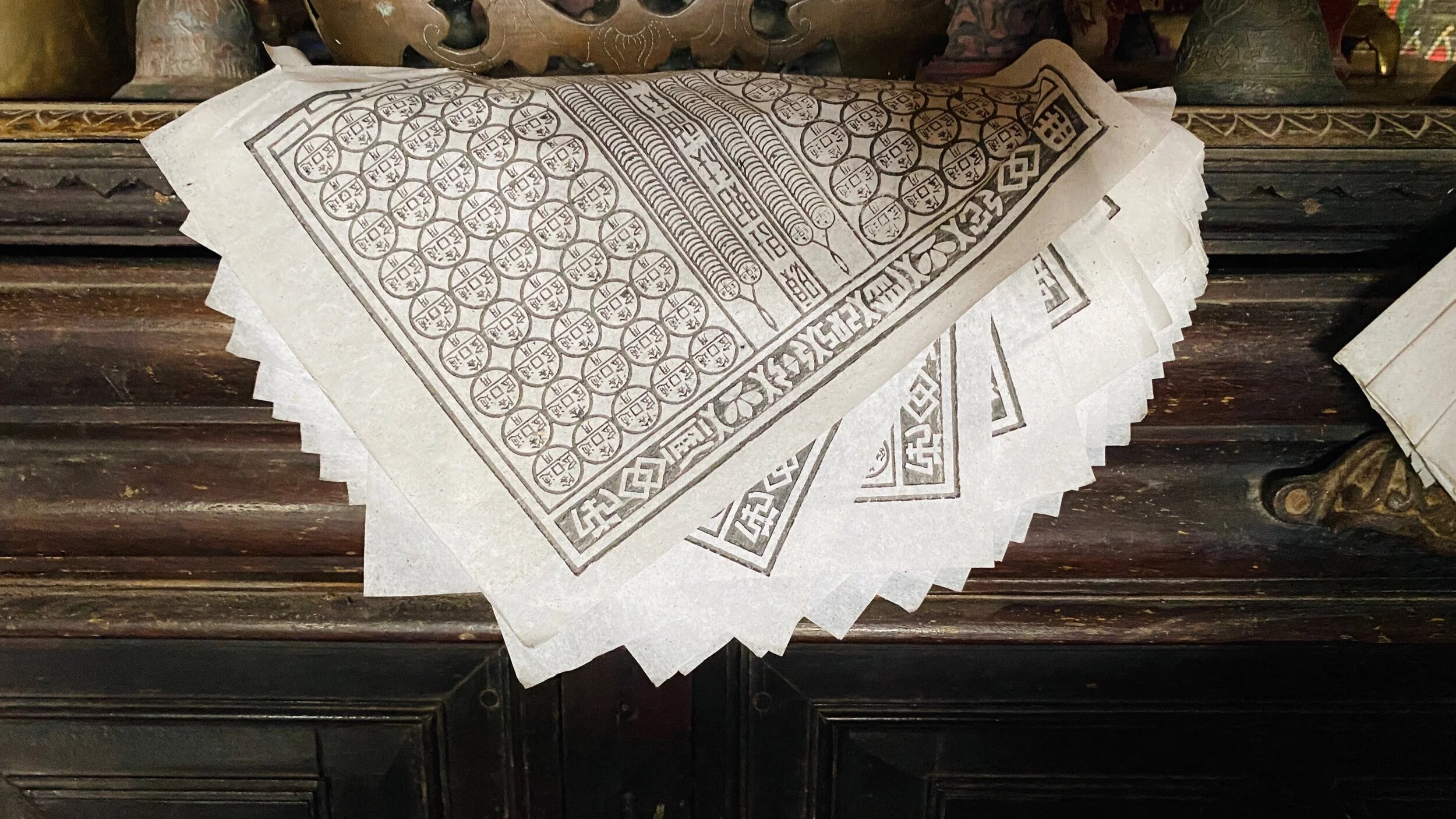

The paneled ceilings of the small halls are in the Chinese crabshell style. The “two swords” decorative rafters on the side walls are also Chinese, as are the yin-yang roof tiles. There are many symbolic carvings throughout, including pumpkins (fertility), ribbons (10,000), batwings (good luck, especially in finance), a lute with ribbons (harmony in marriage), protective “eyes”, and clouds (the mode of transport of the gods) among others. A specialist in Chinese decorative arts could spend hours or days here deciphering everything; there are artistic references to generational continuity, material prosperity, marital harmony, Buddhism and Confucianism.

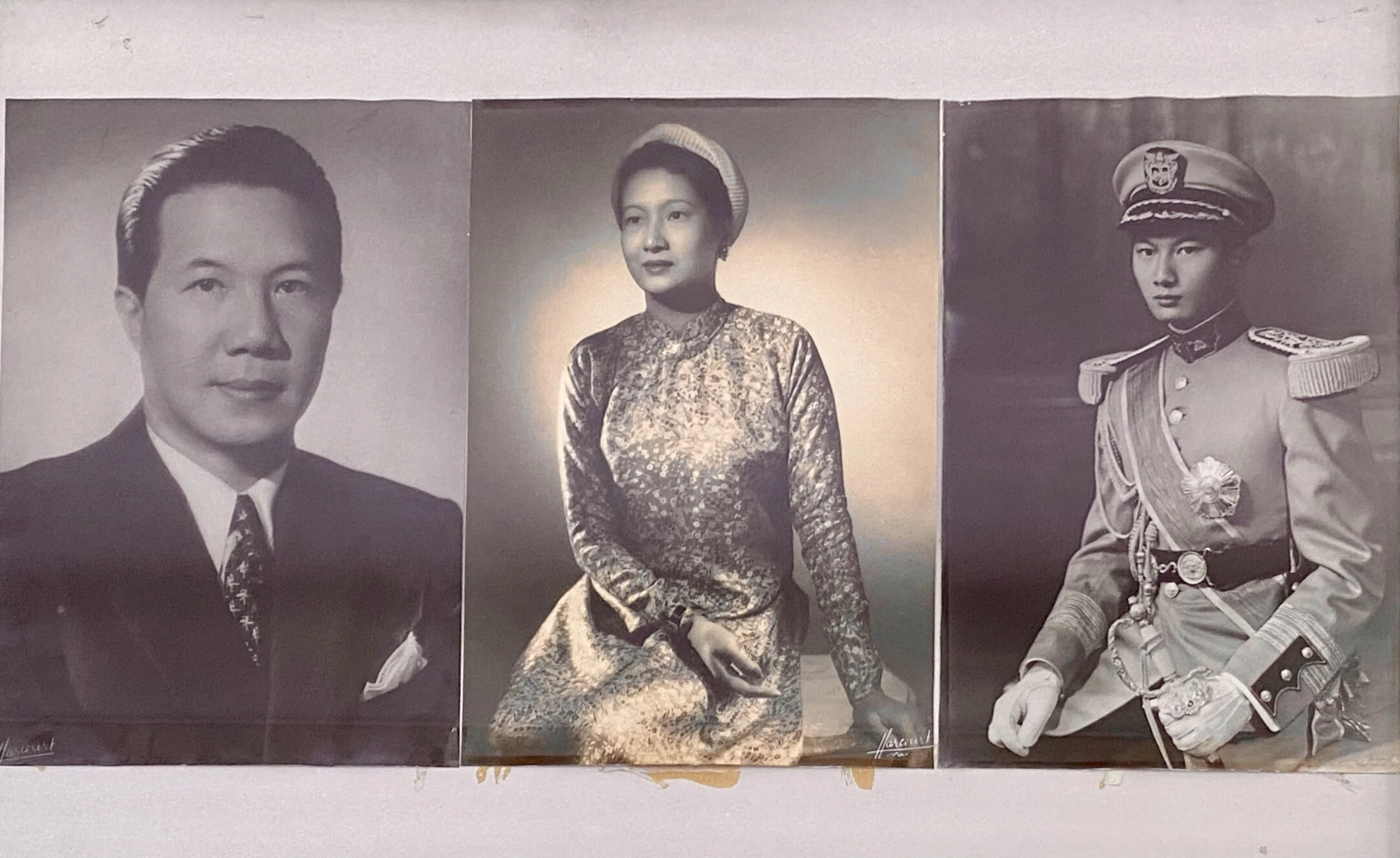

In addition to the architectural details, there are hundreds of valuable antiques to study. These are mostly the personal effects and treasured belongings of the ancestors of the home’s current occupants. Tan Ky means “great progress”; the founding patriarch, Le Tan Ky, earned the honorific by beginning life as a neighborhood orphan named Cong, and becoming one of the richest traders in the city. He purchased the house around 1850, and it has remained in the family for seven generations so far. Currently the family lives upstairs, and downstairs is a house museum. Small antiques are displayed in cases and larger furniture and objects are left where they’ve always been.

Of the many antiques, the two most famous are the Hundred Birds panels and the Confucius cup. The Hundred Birds panels depict 100 Chinese characters as unique mother of pearl birds inlaid in lacquer. In traditional Chinese art, the Hundred Birds motif symbolizes fame, mastery, perfection and leadership. And of course, any sailor knows that seeing birds means your long voyage is all but over.

The Confucius cup is from the 16th century, and demonstrates a story wherein Confucius (thirsty after roaming a desert) was given a special cup of water that emptied itself when filled to the brim, but held water when only partially filled. The lesson is about not getting too greedy, and not letting the desire to be great overrule the habit of being good.

The back house is open to the Hoai river. There are old manual rice hullers, stoves and other items once used by servants, plus parking for the family’s scooters. There’s also a dumb waiter to the second floor, once used to haul down purchases from an upstairs warehouse, for loading onto waiting boats.

Hoi An has always flooded in the winter, and some years are worse than others. Locals like to nostalgically mark the water height in these years, the same way some parents mark their children’s height and age on a door frame. It seems the flooding in the old town has become much worse since the 1990s, when the island opposite the old town was built out. The worst year recorded at Tan Ky house is 1964, but the remaining 8 catastrophic floods were all between 1999 and 2017.

Of all the old houses in Hoi An, this one is absolutely the best. I could have spent much more time eyeing their antiques. I would go back!