Palace 1 was built between 1929 and 1933 by a member of the French colonial elite, Robert Clément Bourgery. Bourgery was almost 60 when construction began, and had already spent 30 years in the Far East, primarily in the French concession outside Beijing (Tien Tsin 天津). The son of an engineer, he also trained as a mechanical engineer and joined the French Expeditionary Force, determined to make his fortune abroad.

In Tien Tsin, he met Li Tin Chu, recently a highly ranked mandarin in the court of notorious Empress Cixi. Li Tin Chu was a diplomat and interpreter who had been converted to Catholicism by his French/English/Latin teacher, a Jesuit priest. This was considered treachery by the anti-foreign dowager empress; he was banished from court, and living at the French consulate as a refugee. Anti-foreign sentiment would reach a boiling point in 1900, when Bourgery defended Tien Tsin during the Boxer Rebellion.

With the rebellion firmly put down, Bourgery and Li were determined to build their fortunes together, combining Li’s connections, language and negotiation skills with Bourgery’s engineering abilities. They formed the Electric Energy Company, and made their first millions bringing electric light to Tien Tsin. They continued building hydroelectric plants in Shanghai and Vietnam and self-sufficient buildings like the Grand Hotel in Beijing (Beijing itself wouldn’t install an electric grid until 1943).

In traditional mandarin fashion, Bourgery married both of Li’s daughters, and their children in turn married French officers, half English/half Chinese girls, etc. The common thread in their family was Catholicism, and they were deeply embedded in the European colonial elite. According to remembrances written by their friends, Bourgery’s grandchildren were so assimilated in China and Vietnam that they didn’t really speak French when they arrived in France as children to attend school.

Bảo Đại bought the house from Bourgery in 1949, when he returned to Vietnam (post-abdication) as its Head of State. Having been exiled in France and Hong Kong, perhaps he was aware of the Bourgery clan before re-entering the social swirl of Dalat and declaring it Vietnam’s new capital. Doubtless he made Bourgery an offer he couldn’t refuse, which conveniently coincided with communist China nationalizing the Bourgery family’s utility companies, and failing to grant them exit visas without substantial bribes. When able, Bourgery family members returned to France, or first decamped to Vietnam, but then were forced to France in short order as the Indochina Wars began.

Perhaps Bảo Đại felt some kinship with Bourgery; his own first wife was Catholic, French reared, and of Chinese descent. In his interview, he tears up speaking about her, and refers to her as the Queen. He discusses visiting the Pope with his family, and letting his children choose their religious beliefs for themselves. And like Bourgery, his brand of devoted Catholicism did not preclude having multiple wives and mistresses (and children by each), requiring all the outhouses conveniently preexisting on the property!

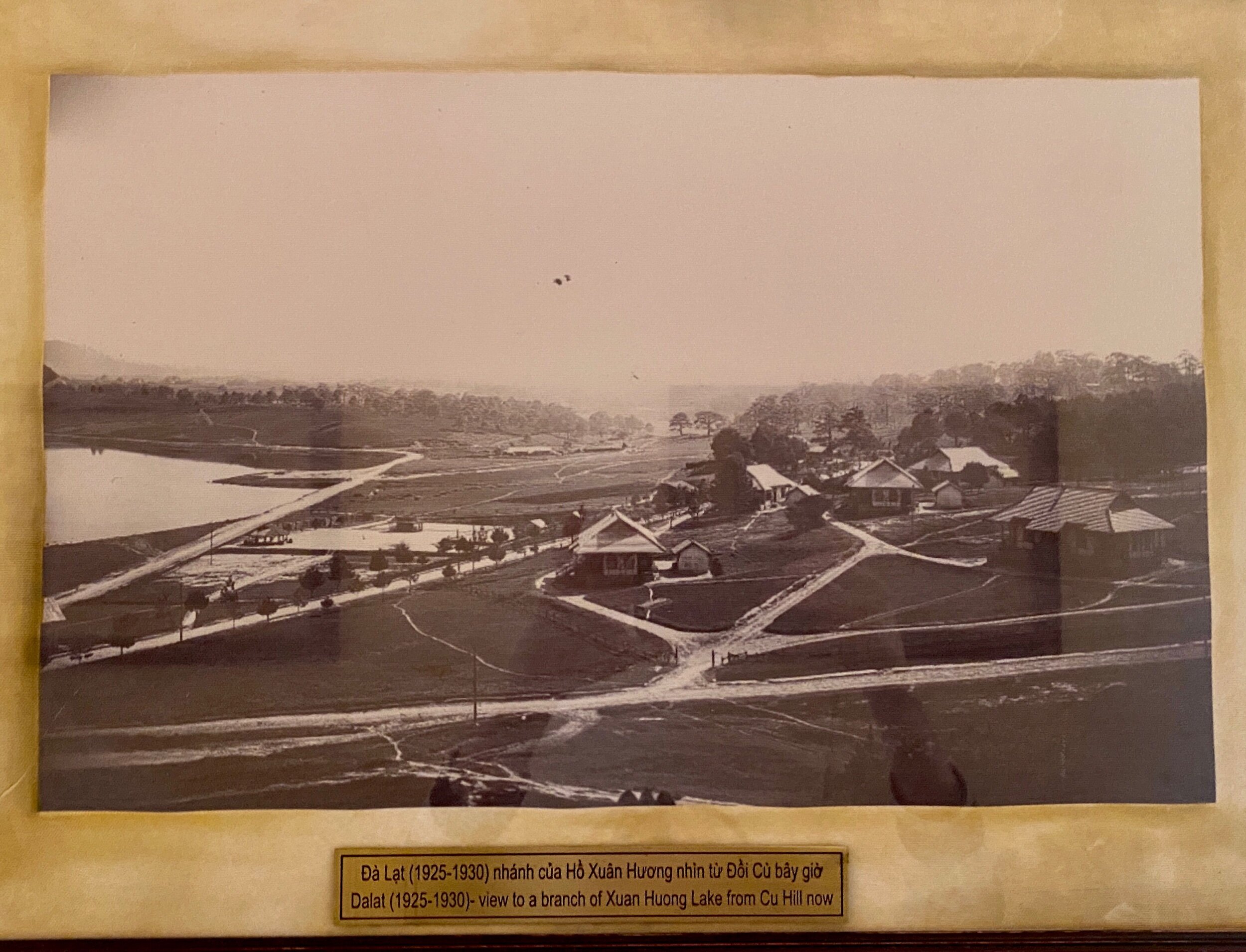

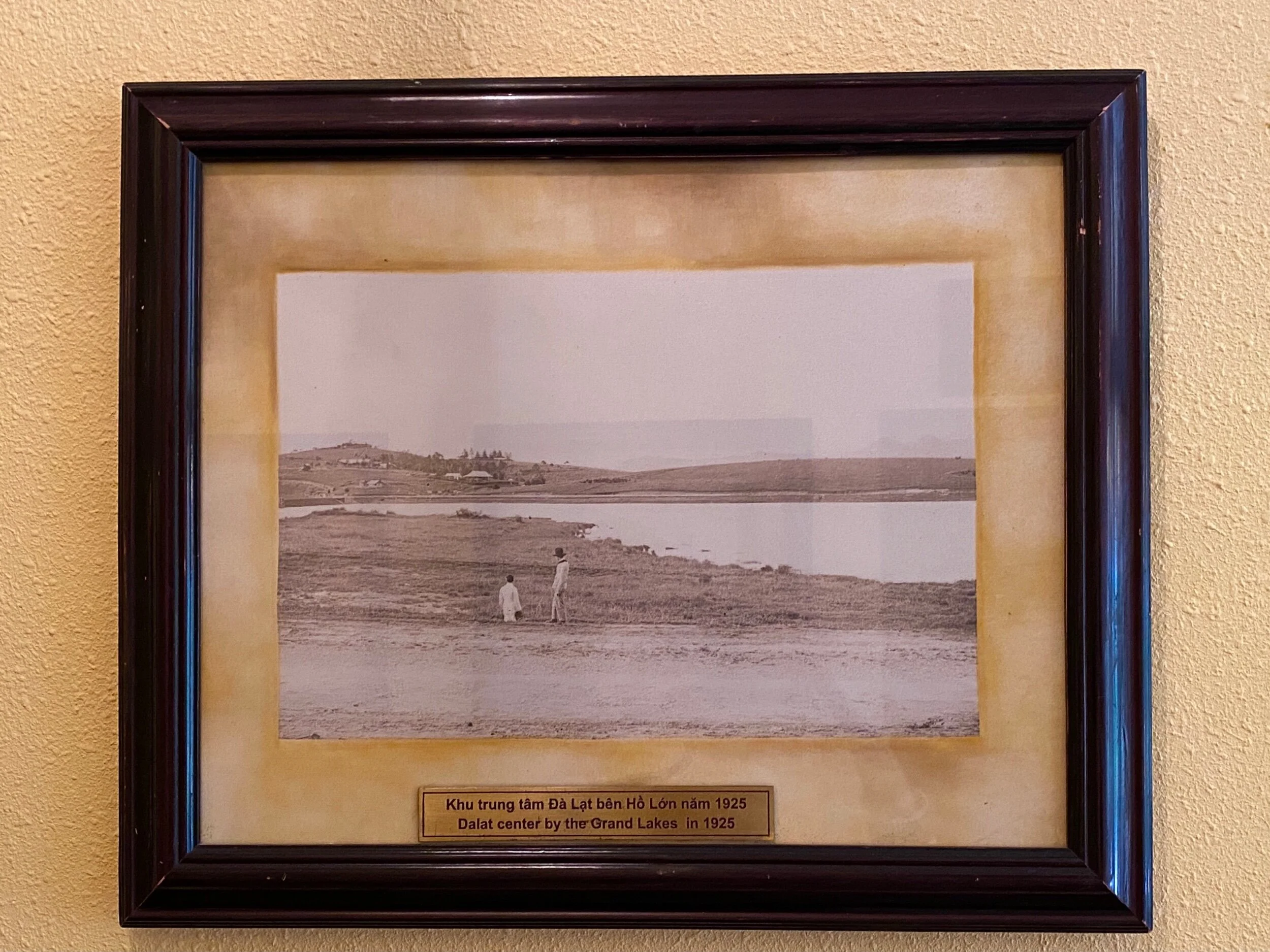

The architecture of the house and its outbuildings is entirely European. Some elements, like the type of roof tiles, wooden shutters, and stone walls, closely resemble houses in le Gard, where Bourgery grew up. Others, like the proportions of the houses, gabled roofs with hanging brackets and decorative mouldings, reflect the Swiss chalet style trendy in the ‘30s. The current view is of ramshackle buildings filling the valley, but at the time, the view was onto Bảo Đại’s own park (apparently he enjoyed hunting with a bow and arrow).

After Bảo Đại’s permanent exile in 1954, the house was used by Ngô Đình Diệm until his assassination in 1963, and then by various other South Vietnamese leaders until 1975. Diệm added a hidden helipad, connected to the house via a secret tunnel behind a bookshelf. After reunification, the house was left to rot for 25 years or so, and then renovated for use as a tourist destination.

As in the other Bảo Đại palaces, the furniture here is a real mismatch for the house, far too cheap and common for men as wealthy as Bourgery, Bảo Đại, and Diệm. And of course, the grounds have been horrifically altered for photo ops, with a Hollywood-style sign, giant chess set, tree of lanterns, allée with a hundred primary color empty birdcages, tacky fountains, and horses pulling Victorian style carriages. The worst/best thing of this sort are mannequins of Bảo Đại and his wife sprinkled throughout the upstairs rooms, that visitors pay extra to take pictures with!

So what transpired in this house? In his interview, Bảo Đại depicts sweeping geopolitical changes as more or less a clash of personalities well known to him.

For example, he speaks of Ngô Đình Diệm (the first president of South Vietnam, his rival and replacement in house and history books alike), as more or less an uppity mandarin he trusted too much as a very young man. Bảo Đại describes Diệm as rather young himself when they first met, from a Catholic family but mandarin caste. He admired Diệm’s intelligence, agreed with his nationalist ambitions for independence, and was shocked when he quit as Minister of the Interior after only 3 months.

Bảo Đại characterizes his own unwillingness to strain against French rule as the fulfillment of his duty to maintain harmony for his people. He says the country was calm and unchanged for many years, which he didn’t think was necessarily a problem, though he desperately wanted to modernize. It was so obvious to him the French would refuse Diệm’s proposals for radical reforms, he found Diệm’s dramatic resignation disingenuous. He was insulted by Diệm’s publicly proclaiming him a French puppet, and returning his seal and honors.

Bảo Đại was only 20 years old, and literally just returned from Paris the year before; he did not understand the urgency of revolutionary fervor in Vietnam, wasn’t clear on exactly how bad French oversight was, and thought gradual change was the way forward. He preferred explicit agreement with the French, and saw subversion as beneath his office.

Diệm was supposedly exiled from political life and surveilled in Huế for the next ten years, but in reality started building his base for “the third way” (non-colonial, non-communist) immediately. It should be noted that Ngô Đình Diệm was likely not imprisoned or exiled because his sister-in-law, Madame Nhu, was Bảo Đại’s first cousin once removed; Bảo Đại was a grandson of Emperor Đồng Khánh, and she a great-granddaughter. Was Bảo Đại playing checkers while Ngô Đình Diệm played chess, or was he proposing a long game that Diệm had no patience for? Did Bảo Đại slowly come to see things Diệm’s way, or was his hand forced by opportunism and greed alone? We’ll never really know.

Both Bảo Đại and Diệm sided with Japan against France during the 1940 axis occupation of Vietnam. Though the Vichy government provided administrative continuity, Japanese officials called the shots. Bảo Đại says both he and Diệm admired the modernity and economic dominance of Japan. Bảo Đại was personally impressed by the mikado, who was not only genteel and charismatic, but worshipped as a god by his people. Diệm was eager to ally with non-European anti-communists. He even secretly cultivated a friendship with anti-colonialist Prince Cường Để (long exiled in Japan), and intended to install him in Bảo Đại’s place, should Bảo Đại not collaborate with him and the Japanese.

Bảo Đại notes that the Japanese forced the kings of Laos and Cambodia to sign declarations of independence as well, and that he held out longer than them (until 1944) so as not to betray Indochinese colonial troops, many of whom were Vietnamese. He mentions that despite his fondness for France, under French rule even the word ‘independence’ was taboo. Meanwhile, the Japanese were handing it to him in name and maybe practice. He claims to have signed only once he realized both French and Japanese forces were spent, and thought an independent Vietnam might have a chance to survive. When Vichy France was liberated by the Allies, and then when Japan surrendered, he felt his dream of sovereignty was secure.

What he didn’t expect was how quickly the Việt Minh were able to fill the power vacuum once Japan surrendered. After Trần Trọng Kim failed to gain popular support as Bảo Đại’s Prime Minister, Diệm rushed northwards to fill the position. However, he was captured by the Việt Minh, exiled to a rural village, and temporarily struck down by malaria. Without an immediately available alternative president and no army of his own, Bảo Đại agreed to abdicate his throne in favor of Hồ Chí Minh, famously offering the communist-friendly rhetoric that he “would prefer to be a citizen of a free country than the king of a slave country”, and agreeing to serve as Hồ’s ‘Supreme Advisor.’

Bảo Đại seemed to evaluate Hồ Chí Minh by the same arrogant, superficial criteria as he did Diệm, saying he trusted Hồ because Hồ was from a mandarin family, and treated him with the extreme deference expected of a mandarin by an emperor. He miscalculated that Hồ’s nationalism was more important to him than his communism, thinking Hồ might be persuaded to accept Vietnam as a department of France, if full French citizenship was granted for all Vietnamese people, especially if that meant alleviating poverty and preventing a war for independence. He believed Hồ signed the Fontainebleau agreements in good faith.

Of course, Hồ wouldn’t be satisfied with anything less than complete independence, and hoped Bảo Đại could negotiate a better deal with his French familiars. Between 1946 and 1947 Bảo Đại signed three successive agreements, each with increasingly strong verbiage about self-rule, but no outright declared grant of independence. Bảo Đại said that with Hồ’s rejection of each agreement, he began to see the Việt Minh not as nationalists, but as communist rebels. Hồ fired and exiled Bảo Đại; Bảo Đại didn’t seem to think he, as the son of heaven, could be fired, and started sarcastically calling Hồ “l’empereur rouge.” He blamed Hồ for plunging Vietnam into war, and passed his next two years in exile as a playboy in Hong Kong and France.

In 1949, the French installed Bảo Đại and his government in this house, and offered them to the Vietnamese people as acceptable leaders in exchange for peace. Naturally, this didn’t inspire enough Vietnamese nationalists to stop fighting, and the war dragged on. Bảo Đại says French awareness of the American desire to fight communism in the region caused France to hold on longer in Vietnam than in the rest of Indochina. Apparently, the French believed they would win with American backup that never arrived.

Going into the Geneva talks in 1953, Bảo Đại had agreed with the French to be named South Vietnam’s ceremonial Head of State, with his old acquaintance Diệm as President, and some limited French oversight or privilege. Just as in the past, Bảo Đại didn’t really see the problem with the French, while Diệm saw them as an obstacle at worst and a stepping stone at best. Again, just as in the past, Bảo Đại took the agreement at face value, and Diệm operated behind the scenes.

Bảo Đại didn’t even attend the peace talks, allowing the French to represent him while he split his time between his chateaux in Cannes and Alsace, making occasional ceremonial visits to Đà Lạt and Huế. This selfish behavior earned him his own nickname, “the emperor of the West.” And then, even as the Geneva peace talks were progressing in 1954, the Việt Minh completely and finally defeated the French at Điện Biên Phủ.

When Bảo Đại learned that France had agreed to withdraw troops, divide Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and hold a national referendum in two years’ time to determine leadership, he initially refused to be the emperor of the South. Why should he lead half of Vietnam when the whole had been his just seven years prior? He also didn’t want to preside over a nation embroiled in civil war.

Of course, Diệm was willing to fill the power void, and continued to build military and diplomatic relations, particularly with America. Just a month after Điện Biên Phủ, Diệm visited Bảo Đại in France with a new deal, offering to be Prime Minister of South Vietnam only if Bảo Đại relinquished all military and civilian control. Bảo Đại agreed, and Diệm and his cabinet were installed in the house.

In 1956, a supposedly fair vote with international observers was held in Saigon, to fulfill the Geneva accords. However, it was blatantly and distastefully rigged for Diệm. Hồ and leaders of other political parties were not on the ballot, allowing the people to vote only for Diệm or Bảo Đại. Witnesses wrote that the Diệm ballots were red (the color of good fortune), while the Bảo Đại ballots were green (the color of bad luck), in a crass effort to sway the illiterate, indifferent and superstitious. Furthermore, voters were explicitly instructed to put the red ballot in the box, and the green ballot in the waste bin; some of those who disobeyed were beaten in the streets by policemen. Most egregiously, over 600,000 votes were supposedly tallied for Diệm, when there were only 450,000 registered voters in Saigon.

Bảo Đại wasn’t present and didn’t campaign. He was accused of simply preferring his extremely luxurious life in France to working for his people; the Vietnamese public didn’t know he had already privately agreed to stay out of it, and was only on offer as a straw man candidate. Having ostensibly lost the popular vote, after 1956 Bảo Đại considered himself formally, officially, and totally released from his inherited duty of service to the Vietnamese people, and never returned to Vietnam.

Bảo Đại says he hoped that once each political group had their own sovereign territory and chosen leader, the fighting would stop. Needless to say, it didn’t. Diệm would rule as the first President of South Vietnam for the next seven years, subduing or absorbing countless political factions and powerful families by force, and amassing untold private armies and secret police. He was able to build incredible wealth for his family through not only overt political means, but through the black market trade in rice (to the starving North and China) and opium (to Laos and Cambodia). On a personal level, war was very profitable for Diệm.

Diệm wasn’t all bad; he founded several universities, negotiated $49 million in reparations from Japan, began a process of land reform and resettlement far more humane than Hồ Chí Minh’s land redistribution system, closed opium dens and brothels, and established diplomatic relations with many first-tier nations. However, his corruption, nepotism, greed, and ego were such that he also suppressed all dissidence in the South with cruel efficiency, executing and disappearing many and allowing his clique to do the same.

Oddly, it was not the persecution of actual dissidents, communists, or spies that led to Diệm’s downfall, but Buddhists. Under his rule, all the old French laws privileging Catholics were maintained. These laws, which exempted Catholics from corvée labor, agricultural contributions, and other types of taxes, had served to stratify and skew colonial society in favor of French culture and business. Diệm increased this Catholic favoritism, going so far as to only give self-defense weapons to Catholic villages. Sons of established families had to join up or lose everything; once in the army or government, they had to convert to Catholicism to qualify for promotions.

With his older brother Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục serving as an archbishop, Diệm corruptly acquired enough urban and agricultural real estate to make the Catholic Church the largest landowner in the country . . . disenfranchising enemies, rewarding accomplices, and enriching the Ngô family in the process. Under the French, Buddhists were able to seek and gain permission to worship, and their role in education and community life was mostly ignored. Under Diệm, Buddhists were no longer allowed to publicly perform their rites or fly their flags, their lands were confiscated, and new, heavy taxes were imposed.

In 1963, conflicts over Buddhist repression came to a head. In June, Thích Quảng Đức, a protesting Buddhist monk, publicly burned himself alive in Saigon, attracting international criticism to Diệm’s oppressive regime. Diệm retaliated by ordering Catholic troops to raid and loot pagodas, confiscate and trash religious artifacts, and beat Buddhist monks in the streets.

Between 70 and 90% of South Vietnamese people were Buddhist, and monks, nuns, and laypeople alike took to the streets in protest. They were tear-gassed, chemically poisoned by airplanes flying overhead, and attacked by police dogs; soldiers threw grenades and shot into crowds. In Saigon, over 200 people were hospitalized and over 1000 monks arrested. In Huế, eight children were killed, and throughout the country more monks self-immolated. The Kennedy administration communicated through diplomatic channels that they would replace Diệm if the “Buddhist crisis” wasn’t quickly resolved.

Though Diệm signed an agreement with Buddhist leaders, it quickly became clear that he wouldn’t honor it. He claimed the Viet Cong were actually responsible for the attacks on protestors, not him; he also said the agreement did not include any privileges Buddhists didn’t already enjoy, so no practical changes would be necessary. In a statement to the press, Bảo Đại’s cousin, the notoriously unpopular First Lady Madame Nhu, told a reporter she thought Kennedy himself was behind the Buddhist problem, and defined her legacy with the appalling suggestion that she’d “be happy to provide foreign gasoline and a match if Buddhists want to have a barbecue.”

JFK, America’s first Catholic president, was duly insulted: first, that Diệm’s sister-in-law would libel him; second, that all this was purportedly done in the name of the Catholic Church. When he publicly denounced the treatment of Buddhists in South Vietnam, Madame Nhu doubled down, telling the press she had overheard an American officer saying the barbecue thing and assumed it was the party line.

While Madame Nhu was muckraking, her father was serving as the Republic of Vietnam’s ambassador to the US, living in Washington, D.C. Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., the ambassador to South Vietnam, told Nhu, Diệm, and her father that she needed to shut up; they responded that it was very un-American to not let a lady use her freedom of speech.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the Americans, France was attempting to negotiate a cease-fire between the North and South, in exchange for the return of some privately owned French property. The North, suffering from terrible famine, wanted to trade their coal for Southern rice, and were willing to temporarily put down their weapons to do so. Nhu leaked key details of one of these secret meetings to the Washington Post.

Though the story was superficially about a potential ceasefire, the easily grasped subtext was that the Kennedy administration wasn’t privy to important dealings of the RVN, the RVN was ready, willing, and able to broker peace with North Vietnam on their own or with alternate allies, and (most damningly) the situation in Vietnam was not as the American public had been led to believe.

The underlying message, confirmed through diplomatic channels, was that in Diệm’s opinion, the US needed South Vietnam as a regional bulwark against communism more than South Vietnam needed the US to continue fighting; so if Kennedy embarrassed them again by further criticizing their treatment of Buddhists, Diệm might go farther than blaming and defaming Kennedy, and really make his own separate peace with the communists.

Displeased with the rampant corruption under Diệm, different generals had been pitching coup plots to the Americans for years, but wouldn’t move forward without their support, which had never been granted. Now, many in both the Kennedy administration and Diệm’s own government felt Diệm was not only wasting time, weapons, and credibility in his vendetta against the Buddhists, but that his greed and ego were being prioritized over their victory.

Diệm’s suggestion that he would allow North Vietnam to persist as a communist state was the tipping point. The CIA immediately recruited three RVN generals and two corps commanders to an assassination plot. Less than two months after the Washington Post article was published, Diệm and Nhu were shot in the back of a car.

Madame Nhu and her oldest daughter were shopping in Beverly Hills when her husband was murdered; her younger children were helicoptered out of this Dalat house and flown to Rome to stay with Thục, who happened to be there for a Vatican conference. Three weeks later, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. He is on record as having called Madame Nhu “a goddamn bitch,” and blamed her for instigating the murder of her own husband and turning the tide against the entire Diệm government with her nasty remarks.

The house, already rarely used, was used even less by the new administration. The Bourgerys, Bảo Đại, and Madame Nhu all lived their lives out in exile. The war went on for another 15 years; obviously, the communists won.