All tourist cities in Vietnam have night markets, and they become boring after a while. It’s typically sketchy merchandise, sketchy street food, really aggressive vendors, swarms of locals who don’t have the same cultural norms about personal space . . .

I’ve become so unimpressed by them that I considered skipping the Phú Quốc night market, and I am so happy I didn’t! It is small but excellent. Of course there is junk for sale and some seafood that looks more dead than alive, but the good stuff here is really really good.

I wouldn’t buy pearls here, but there are huge natural shells for just a few bucks, the type decorators pay $40+ each for in New York. There are also tons of seafood options, though scams are the norm (do NOT believe the 20k BBQ signs, your meals will magically come out to $10-$15 per person)! The atmosphere is obviously a loud open air party type atmosphere.

The market supposedly opens 4:00PM - 11:00PM daily; I think 4 is a bit early and it’s better to go for dinner or just after. Weekends are best if you really want to experience the scene.

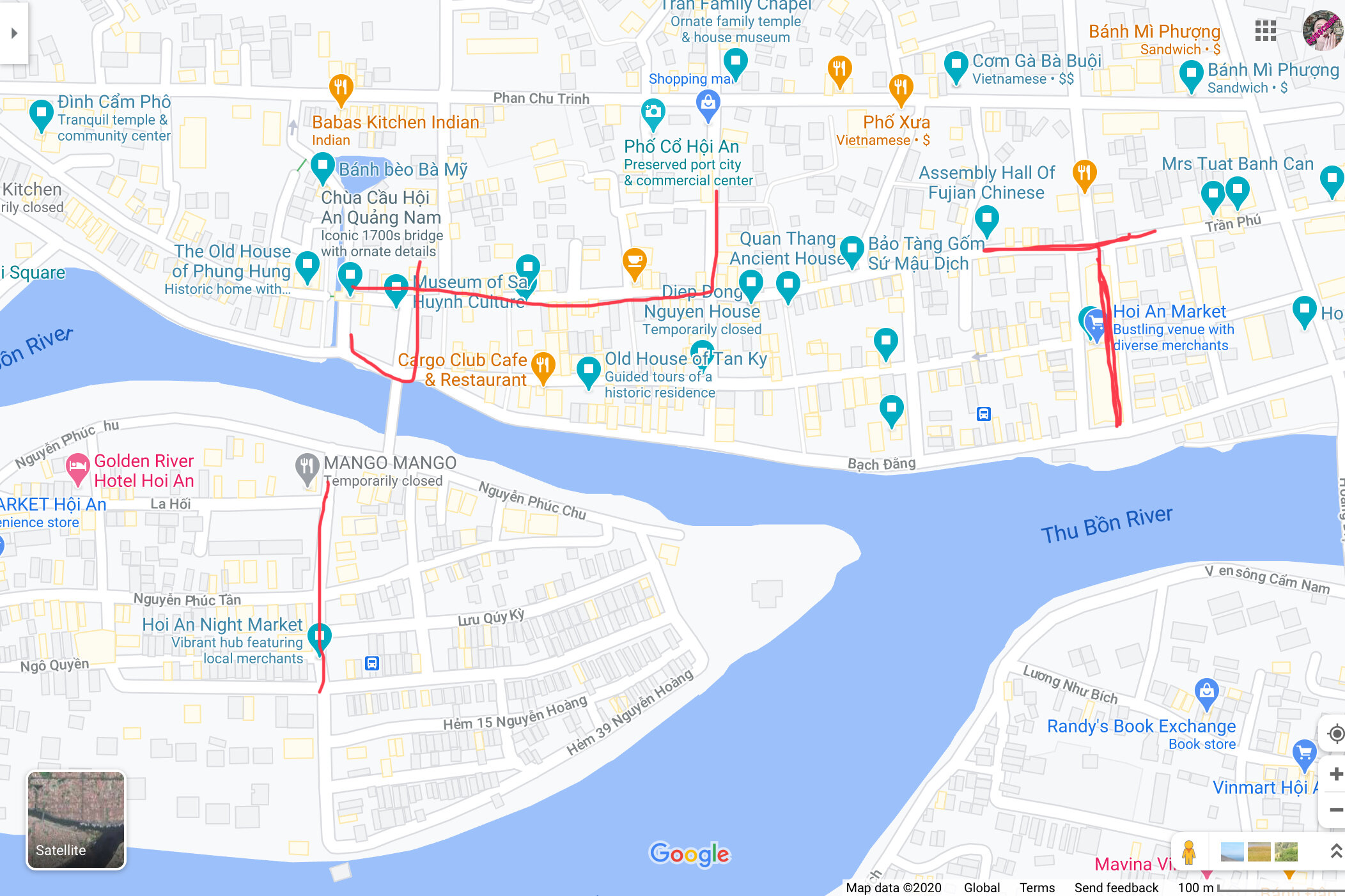

On google maps you’ll see many locations listed as Chợ Đêm Phú Quốc, or “night market” in a couple other languages, and think, well which one is it? The answer is, all of them. The spots on google maps loosely mark the perimeter. I would say the main drag is along Đường Bạch Đằng, but it stretches down side streets and wraps around a few blocks, with the local restaurants in Dương Đông participating too. If you’re taking a cab and want to get as close as possible, ask the driver to take you to the Cao Đài Temple. That’s about one block away from the action, which you will be able to plainly see.

There’s also old info online and a google maps spot for the Dinh Cau night market. This is not what you want! That’s just a couple daytime fruit sellers and a taxi stand. Have fun!